You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Hades IRBM (France)

- Thread starter scorp

- Start date

-

- Tags

- armée de terre chemical / biological weapons cold war federal republic of germany force hadès france french fifth republic intermediate range ballistic missile irbm north atlantic treaty organisation nuclear battlefield post-cold war pre-strategic sub-strategic nuke tactical nuke west germany western europe

Mercurius Cantabrigiensis

ACCESS: Restricted

- Joined

- 8 November 2007

- Messages

- 46

- Reaction score

- 19

Mercurius Cantabrigiensis said:This poor-quality drawing is the only one I have.

From "Les missiles balistiques", COMAERO, 2004

Attachments

You're welcomeflateric said:Oh, thanks a lot!

I am not familiar with the interface. I suppose I used a wrong procedure trying to insert the image.

bechar06

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 6 August 2014

- Messages

- 13

- Reaction score

- 13

Perhaps 2 other tracks about le HADES IRBM:

http://www.artillerie.asso.fr/basart/article.php3?id_article=1304

http://www.artillerie.asso.fr/basart/article.php3?id_article=1304

Last edited:

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 7,901

- Reaction score

- 13,348

HADES was an SRBM wasn't it?

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

They were initially kept in storage for exactly such a contingency, but they were infamously ordered destroyed by President Chirac in 1996/97.

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 7,901

- Reaction score

- 13,348

For a while they did but the last were scrapped in 1997.Does anyone know if the cunning Franch kept Hades in storage so that they can be used to counter Russia and give the EU an alternative to US weapons that may not be available?

Last edited:

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

A bit on the system and it's planned employment from French Security and Defence Policy: Current Developments and Future Prospects (Fredrik Wetterqvist, DIANE Publishing, 1990):

The Army's future prestrategic nuclear weapon, the mobile Hadès missile (dual-capable) with a 350-500 km range and ability to carry a 10-to-25 kt nuclear warhead, a neutron bomb, a conventional warhead or chemical agents, will replace the ageing Pluton SRBM in 1992. In April 1989, France, reportedly, could manufacture 200 Hadès missiles with 20-60 kt warheads, with an expected initial order of 90 units (Webster, 1989a:4). Other sources put the warhead capability at 80 to 100 kt (Westerlund 1990:44). The French Army plans to purchase altogether 180 Hadès missiles (SIPRI, 1989:32).

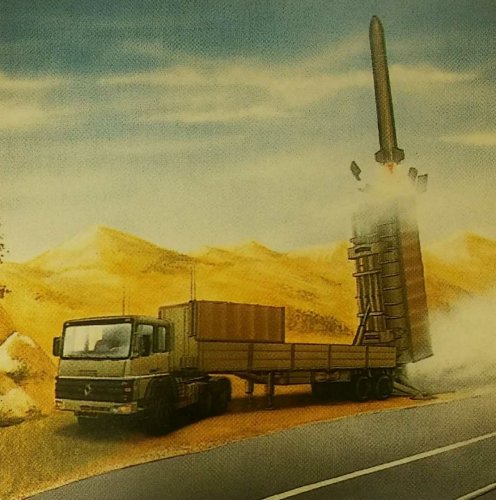

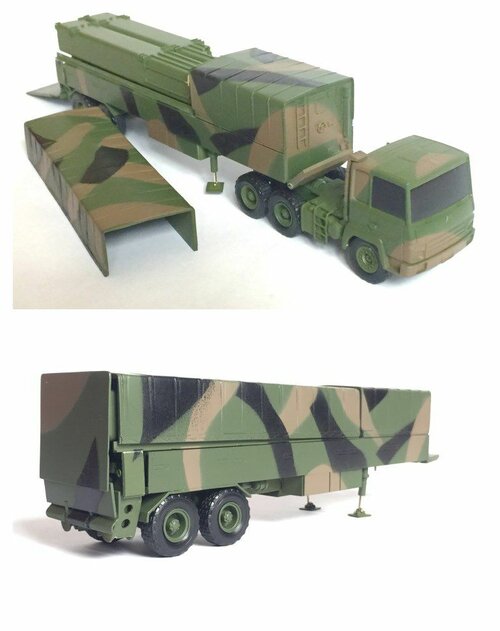

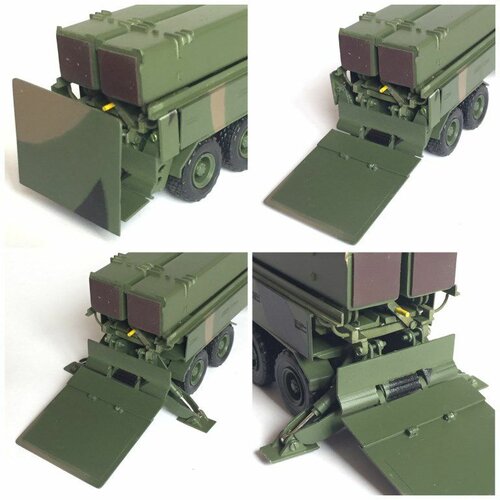

The Hadès division will comprise three artillery regiments, and the first will be installed with the 15th Artillery Regiement at Suippes in the Marne region of eastern France. The second will be stationed with the 3rd Regiment at Mailly in the Aube region, also in eastern France. The details concerning the final third have yet to be decided, but Belfort has been mentioned. The Hadès division will also have the RITA communications net, a Mistral surface-to-air missile battery and a support battalion (Isnard, 1989:419). The Hadès system will be disguised to resemble a semitrailer, which will be capable of carrying two 7.2 metres missiles with inertial guidance systems powered by solid propellant motors (Westerlund, 1990:44).

The French Chief of Defence Staff, General Maurice Schmitt, has said that France would not be prohibited from relocating the Hadès missile into the FRG, which is the case with the Pluton missile (Air et Cosmos, 1989b:5). Mitterrand has stated on several occasions that the missiles are only of 'final warning' characters and are not to be used as battlefield weapons. However, the fact is that if the missiles can be moved into the FRG, it will greatly expand French power alongside Allied forces, and may also serve to lower German anxiety that the missiles would fall on German territory.

The Hadès missile is supposed to be placed under the command of the of the Chief of Defence Staff, thereby, in fact, opening up the possibility of using it as a battlefield weapon. It also has the deterrent value in that it is permanently situated in Europe, because of its mobility, and is expected to be less easily intercepted by enemy missile defences. Critics say that it makes the doctrine of 'the weak against the strong' outdated, and is a step closer to the NATO doctrine of 'flexible response'. Supporters say that it is a sign that France no longer accepts isolation from its European allies, and has started to build on a common European defence (Isnard, 1988e:31).

Although the deployment of the Hadès missile has become increasingly sensitive because of the German unification plans, France has no plans to scrap the missiles. The Chief of Defence Staff, Maurice Schmitt reportedly said that the reduced force levels proposed so far in the START talks are still too high to attract French participation (Isnard, 1990e:28). According to Jaques Isnard, France could very well decide unilaterally to cut the Hadès regiments from three to two, but the possible use of the missiles will remain ambiguous. Minister of Defence Jean-Pierre Chevènement is even reported to have said that the old Tous Azimuths Doctrine is now more than ever real (see chapter 2). In other words, France's nuclear deterrent is not directed at any particular enemy, but in all directions...(Isnard, 1990e:28).

Last edited:

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

I'm still looking though different sources, so I'm not sure if it was a unitary warhead, an ICM (Improved Cluster Munitions) equivalent, or a choice between the two. I have come across however that there was yet another nuclear warhead available, this one in the 150-300 kiloton range and intended for use against Soviet Operational Maneuver Groups before they could enter West Germany.

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 7,901

- Reaction score

- 13,348

Is that the one used on the ASMP/ASMP-A? The TN-80/81 had a 300kT and a weight of 200kg.I'm still looking though different sources, so I'm not sure if it was a unitary warhead, an ICM (Improved Cluster Munitions) equivalent, or a choice between the two. I have come across however that there was yet another nuclear warhead available, this one in the 150-300 kiloton range and intended for use against Soviet Operational Maneuver Groups before they could enter West Germany.

It was using DSMAC, so a unitary warhead seems more likely, since you don't really need a 5m CEP with cluster munitions. Not sure whether the range was the same as the nuclear version due to the heavier warhead though.

Last edited:

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

It seems likely. Interestingly, the OMG countering mission was faded into the background (but not dropped) in 1988 when President Mitterrand assured Germany that Hades would not used against targets on German soil, east or west. It wasn't for nothing that Hades was nicknamed the 'Diplomatic Missile'.Is that the one used on the ASMP/ASMP-A? The TN-80/81 had a 300kT and a weigh of 200kg.

The range of the conventional warhead would have been around 480km. The range with the 300kt warhead would have been just over 400km (enough to cover the Inner German Border). The full 500km range would have been with the default nuclear warhead. Range with the originally planned 25kt warhead would have probably been a fair bit more. No details available on the Enhanced Radiation Weapon [neutron bomb] warhead apart from the fact that it existed in at least prototype form (officially France hadn't built any, but they were very confident that they could deploy ERW warheads in a hurry if and when required). The range of the chemical warheads would have varied depending on what they were filled with, dispersion mode, etc.Not sure whether the range was the same as the nuclear version due to the heavier warhead though.

Last edited:

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

The warhead was to be the TN-90 with a 80 kT power.

Indeed, with the upper yield being 100 kilotons as far as I'm aware.

Last edited:

bechar06

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 6 August 2014

- Messages

- 13

- Reaction score

- 13

from : https://www.senat.fr/rap/r10-733/r10-73359.html News about the HADES trajectory :

"the Russians developed the SS-26 Iskander, the Chinese the M9, the Syrians the M600 and the Iranians the Fateh 110. None of these missiles use new technologies. We French had already used these technologies for the Hades prestrategic missile. These missiles have a peculiarity. They fly in the atmosphere, under 60 to 70 kilometres, and when they go into the dense layers of the atmosphere, 25 or 30 kilometres away, they acquire a manoeuvring capability that makes them virtually impossible to intercept. The interception of these missiles must therefore take place between 25/30 and 60/70 kilometres."

"the Russians developed the SS-26 Iskander, the Chinese the M9, the Syrians the M600 and the Iranians the Fateh 110. None of these missiles use new technologies. We French had already used these technologies for the Hades prestrategic missile. These missiles have a peculiarity. They fly in the atmosphere, under 60 to 70 kilometres, and when they go into the dense layers of the atmosphere, 25 or 30 kilometres away, they acquire a manoeuvring capability that makes them virtually impossible to intercept. The interception of these missiles must therefore take place between 25/30 and 60/70 kilometres."

Would anyone possibly possess illustrations of the TEL for this missile, which was supposed to replace Pluton? Thanks.

materiel-militaire.com is for sale | HugeDomains

Choose a memorable domain name. Professional, friendly customer support. Start using your domain right away.

www.materiel-militaire.com

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,053

- Reaction score

- 8,510

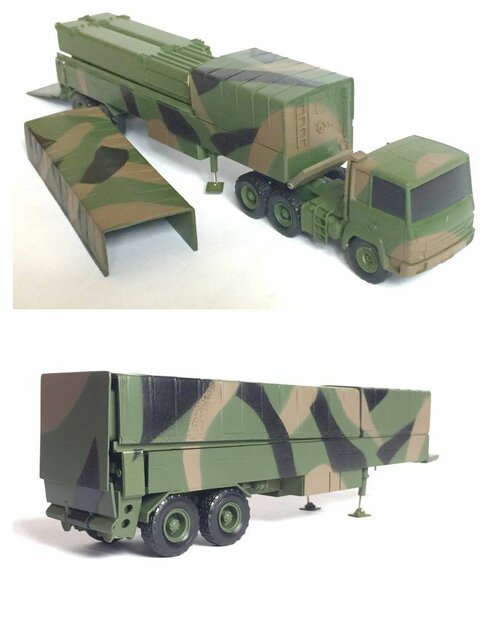

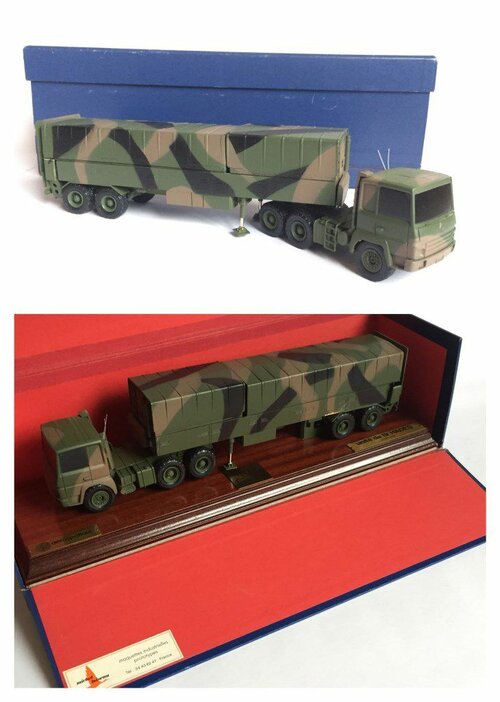

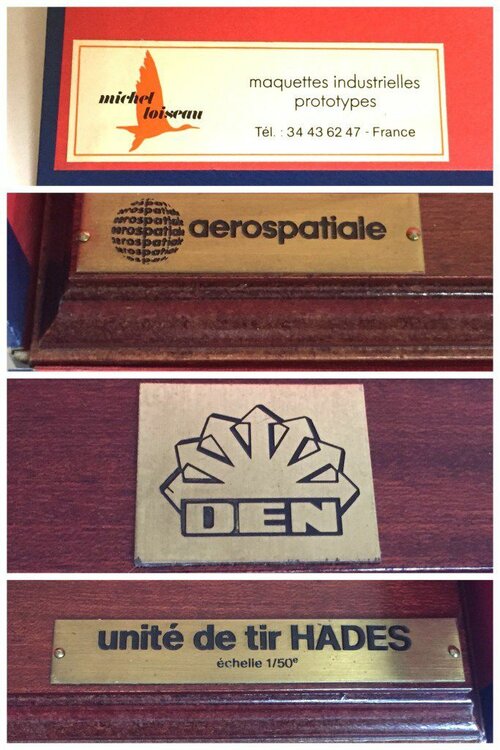

Renault R390 et remorque Lohr érectile lance-missile HADES au 1/50 (par J. Hadacek) MAJ 6/04/19 -

Source photo : www.maquetland.com -29 mars 2019 (MAJ 6/04/19) : RENAULT R390 et remorque LOHR érectile lance missile HADES Maquette Michel LOISEAU 1/50 Peu d’informations et de photos ont circulé sur cette force de dissuasion mobile qui a remplacé le...

Attachments

-

image_1477387_20190318_ob_1e048e_photo-a-de-presentation.jpg11.6 KB · Views: 94

image_1477387_20190318_ob_1e048e_photo-a-de-presentation.jpg11.6 KB · Views: 94 -

ob_a5f538_photo-d.jpg70.3 KB · Views: 67

ob_a5f538_photo-d.jpg70.3 KB · Views: 67 -

ob_f7c696_photo-e.jpg60.6 KB · Views: 65

ob_f7c696_photo-e.jpg60.6 KB · Views: 65 -

ob_f41e86_photo-f.jpg47.9 KB · Views: 64

ob_f41e86_photo-f.jpg47.9 KB · Views: 64 -

ob_a04f4d_photo-b.jpg82.6 KB · Views: 59

ob_a04f4d_photo-b.jpg82.6 KB · Views: 59 -

ob_c64e48_photo-c.jpg125.4 KB · Views: 63

ob_c64e48_photo-c.jpg125.4 KB · Views: 63 -

ob_03c418_photo-e.jpg60.6 KB · Views: 62

ob_03c418_photo-e.jpg60.6 KB · Views: 62 -

ob_b12648_photo-l.jpg65.6 KB · Views: 55

ob_b12648_photo-l.jpg65.6 KB · Views: 55 -

ob_ebba49_photo-m.jpg69.9 KB · Views: 52

ob_ebba49_photo-m.jpg69.9 KB · Views: 52 -

ob_f53ac3_photo-d.jpg70.3 KB · Views: 52

ob_f53ac3_photo-d.jpg70.3 KB · Views: 52 -

ob_76470a_photo-g.jpg60.4 KB · Views: 49

ob_76470a_photo-g.jpg60.4 KB · Views: 49 -

ob_a09d7a_photo-h.jpg40.7 KB · Views: 49

ob_a09d7a_photo-h.jpg40.7 KB · Views: 49 -

ob_9ad36d_photo-k.jpg67.4 KB · Views: 48

ob_9ad36d_photo-k.jpg67.4 KB · Views: 48 -

ob_bf1ab0_photo-j.jpg59.1 KB · Views: 51

ob_bf1ab0_photo-j.jpg59.1 KB · Views: 51

- Joined

- 1 April 2006

- Messages

- 11,053

- Reaction score

- 8,510

Attachments

-

![121497.mp4_snapshot_13.02_[2024.01.05_13.40.08].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251455-b8171e73e2333b9db318abfd46e9df86.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_13.02_[2024.01.05_13.40.08].jpg188.7 KB · Views: 72

121497.mp4_snapshot_13.02_[2024.01.05_13.40.08].jpg188.7 KB · Views: 72 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_13.01_[2024.01.05_13.39.52].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251454-1fcd9fb9365ec55e374acca264d22b7c.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_13.01_[2024.01.05_13.39.52].jpg185 KB · Views: 70

121497.mp4_snapshot_13.01_[2024.01.05_13.39.52].jpg185 KB · Views: 70 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_13.00_[2024.01.05_13.39.46].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251453-7c2497d7c12fc8a625684f1b1c70b0a9.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_13.00_[2024.01.05_13.39.46].jpg203.8 KB · Views: 58

121497.mp4_snapshot_13.00_[2024.01.05_13.39.46].jpg203.8 KB · Views: 58 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_12.53_[2024.01.05_13.39.16].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251452-7a0fb1085ec9f455cc9771af75f6f0c4.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_12.53_[2024.01.05_13.39.16].jpg224.1 KB · Views: 60

121497.mp4_snapshot_12.53_[2024.01.05_13.39.16].jpg224.1 KB · Views: 60 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_12.54_[2024.01.05_13.39.32].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251451-d2dfab322212ed4e2673b77e90888911.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_12.54_[2024.01.05_13.39.32].jpg234.6 KB · Views: 60

121497.mp4_snapshot_12.54_[2024.01.05_13.39.32].jpg234.6 KB · Views: 60 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_12.58_[2024.01.05_13.39.40].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251450-5b5a3105a5d38aa966d33ce801576c19.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_12.58_[2024.01.05_13.39.40].jpg225.8 KB · Views: 67

121497.mp4_snapshot_12.58_[2024.01.05_13.39.40].jpg225.8 KB · Views: 67 -

![121497.mp4_snapshot_13.05_[2024.01.05_13.40.16].jpg](/data/attachments/251/251456-c64e2c2a52d5c020992a2f112e4de512.jpg) 121497.mp4_snapshot_13.05_[2024.01.05_13.40.16].jpg105.9 KB · Views: 86

121497.mp4_snapshot_13.05_[2024.01.05_13.40.16].jpg105.9 KB · Views: 86

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 7,901

- Reaction score

- 13,348

Does the warhead separate from the body, or is it single-piece?

Does the warhead separate from the body, or is it single-piece?

According to "Les missiles balistiques", COMAERO, 2004, Hades did not exceed an altitude of 70 km and the warhead did not separate from the vehicle. This required a reinforcement of the structure but allowed maneuvers at the end of the trajectory.

Hades did not exceed an altitude of 70 km and the warhead did not separate from the vehicle.

So basically a sophisticated French SS-1 Scud?

With a mass of less than 2 tons and a diameter of 52 cm, Hades is much smaller than a Scud even if it has an equivalent range.So basically a sophisticated French SS-1 Scud?

A Tentative Fleet Plan

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 9 April 2018

- Messages

- 1,163

- Reaction score

- 2,586

Terminal maneuvers make this closer to the Iskander in terms of capability.

Forest Green

ACCESS: Above Top Secret

- Joined

- 11 June 2019

- Messages

- 7,901

- Reaction score

- 13,348

Scud was pure ballistic like the V-2 it was based on I think.So basically a sophisticated French SS-1 Scud?

Terminal maneuvers make this closer to the Iskander in terms of capability.

So then French SS-26 Stone?

- Joined

- 3 September 2006

- Messages

- 1,432

- Reaction score

- 1,354

Hadès wasn't meant as a missile to be used during the course of normal combat.

Its role was "pré-stratégique", ie the last desperate warning before launching full nuclear ICBM armageddon.

The thinking was that if the WarPac hordes rushed through West Germany towards France, the French 1ere Armée on the Rhine would make a last stand to cause an accumulation of Soviet forces in front of it (within FRG and CHE), and the Hadès would be launched on that concentration as the final warning that France will escalate.

For some reason, the West Germans and the Swiss did not really like this plan...

Its role was "pré-stratégique", ie the last desperate warning before launching full nuclear ICBM armageddon.

The thinking was that if the WarPac hordes rushed through West Germany towards France, the French 1ere Armée on the Rhine would make a last stand to cause an accumulation of Soviet forces in front of it (within FRG and CHE), and the Hadès would be launched on that concentration as the final warning that France will escalate.

For some reason, the West Germans and the Swiss did not really like this plan...

For some reason, the West Germans and the Swiss did not really like this plan...

Gee, I wonder why

I've also read sometimes that French generals joked about their tactical nuclear missiles' range only being sufficient to reach targets in Germany being an advantage rather than a failure...Gee, I wonder why?

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,147

- Reaction score

- 12,249

Source please?I've also read sometimes that French generals joked about their tactical nuclear missiles' range only being sufficient to reach targets in Germany being an advantage rather than a failure...

Similar threads

-

-

-

S-4 and S-45 IRBM projects (France, Cold War)

- Started by Grey Havoc

- Replies: 6

-

-