Hi everyone,

I recently finished reading "Eagles of Mitsubishi" by Jiro Horikoshi.

Quite a well-written and informative book in my opinion!

Some observations:

- Horikoshi gives an overview over the requirements of the specifications for the 12-shi fighter. While he states that there were "nearly twenty items", he lists only 10. The translator muddies the waters by providing a foot note on range, which is not listed by Horikoshi, without clearly stating that this was part of the specifications. Of course, I'd have very much preferred to see a complete list of the specifications Horikoshi had to try and fulfill.

- Horikoshi considers the elliptical wing used on the A5M conventional and makes it clear that it was a deliberate design decision to give the A6M a different wing planform. Considering just how great an achievement the elliptical planform is usually considered to have been on the Spitfire, I'd have been very interested in his motivation for that change, but it's not mentioned.

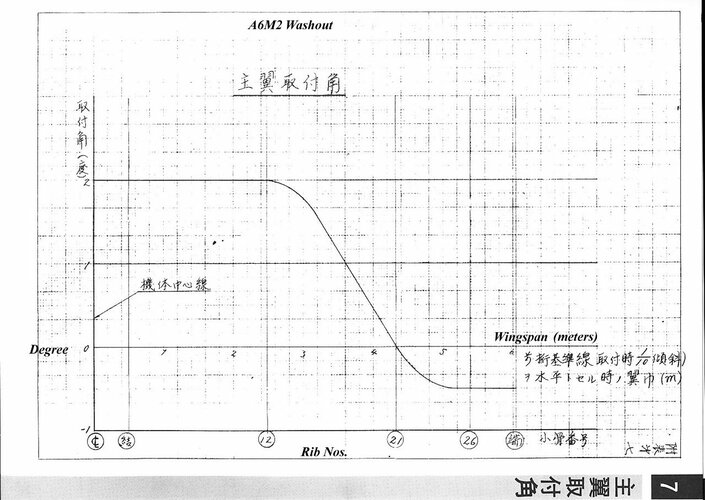

- Horikoshi stresses the great advantage of wash-out on the A6M's outer wings and seems to consider it something of a novelty. Since wash-out was a well-established design technique even in WW1, I suspect that there must be more behind it than the book managed to convey (to me, at least

- In Mikesh's book on the A6M, there is a description of the aileron balance tabs reversing their function depending on the position of the flap selector. This is something also pointed out in John Deakin's report on flying the Confederate Air Force's restored Zero. Though the balance tabs get a lot of room in the book, probably because they lead to a fatal accident of one of the prototypes, this (to my limited knowledge, unique) feature is not mentioned, unfortunately.

- Horikoshi explains (in very broad terms) the methods used to achieve the required G load limit. I had read online that he wasn't happy with the safety factor of 1.8 and designed the Zero to 1.5 instead, but after reading his book, I would say that is a misunderstanding as he merely changed the way the strength of thin members in compression was calculated to allow for their greater range of reversible distortion. The safety factor actually achieved on the Zero apparently was just a shade under 1.8 G.

- The discussion of the elevator control system that avoided excessive authority at high speeds by the deliberate introduction of elasticity in the control circuit was quite interesting. To my surprise, this was actually picked up on by the US evaluators and described in a wartime NACA Memorandum authored by H. W. Phillips. I don't know why I've never heard about this before, as it's perfectly foot-noted in Horikoshi's book. The report, along with a more complete one on the combat-relevant characteristics of the A6M, can be found on the NACA's wiki page on Phillips: https://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/William_Hewitt_Phillips

- Horikoshi explains that they were using a 1:8 model in Mitsubishi's wind tunnel for developing the A6M. He doesn't mention the origin and the characteristics of the airfoil he chose for the A6M, the Mitsubishi 118, but I suppose it was probably also based on work done by Mitsubishi in the same wind tunnel. That's something I'd have liked to read more about.

- The A6M's design history has quite an interesting parallel to the development of the Me 109*, in a way: Willy Messerschmitt was unhappy with the Luftwaffe's specifications and expressed his concerns at the RLM, receiving permission to exceed the specified wing loading (at the expense of manoeuvrability, obviously) in his design. (The motivation was that the fighter, designed as specified, in Messerschmitt's opinion would have been unable to catch the high-speed bombers that were under development at the time.) Likewise, Jiro Horikoshi reached a point in the design process when he considered it impossible to fulfill all requirements, and at a meeting with the Navy asked if one or possibly two of the requirements could be dropped. It seems that suggestion was seriously considered, but then rejected.

- Horikoshi mentions the conflict between requirements for speed and for manoeuvrability. There was actually one meeting with the Navy in which Lt. Comdr. Minoru Genda (apparently representing the voice of the front line fighter pilots) and Lt. Comdr. Takeo Shibata (of the "fighter specialist group") hotly debated the question of manoeuvrability vs. performance. Genda, based on the success of the A5M in China, ranked manoeuvrability higher. Shibata favoured speed and range, arguing that skill could overcome manoevrability limitations, but no amount of skill could make the plane go faster or fly farther than its maximum range.

- There was actually a moment in which the Navy wavered in its otherwise cast-iron determination to have all requirements met, and that lead to Horikoshi calculating an alternative design for the A6M which featured a shorter range, a reduced aramement of only two 7.7 mm machine guns, and a smaller wing, in order to give the type better suitability for the "interceptor" role.

- The reason Horikoshi gives for the engine choice was a bit surprising to me, as he considered the opinion of the fighter pilots to be the decisive factor, and though they would not agree to a larger aircraft. Accordingly, he chose the slightly smaller and less powerful Nakajima Sakae radial over the higher-powered Mitsubishi Kinsei, actually feeling justified in his decision based on the initial comments the fighter pilots made when inspecting the mock-up for the first time. As (if I remember it correctly) as early as 1943 the Navy requested the design of an A6M variant with the Kinsei to improve the Zero's performance, I'm not sure that the original choice was indeed as obviously correct as Horikoshi thinks.

- The book contains a lot of clues to the limitations of the Japanese industry at the time, including a description of how the aircraft produced by Mitsubishi were delivered to the somewhat distant airfield they could take-off from by way of ox cart. How narrow the industrial base was for me was quite striking, considering that Mitsubishi as one of the two leading aircraft manufacturers was unable to pursue even two out of the three tasks of converting the A6M to the Kinsei, developing the succssor A7M, and developing the land-based J2M at the same time. Germany had engineering man-power shortages too, but the Japanese situation seems to have been even more serious. At least, that's my uninformed impression!

- Trivia: Horikoshi witnessed the Doolittle Raid from the design bureau office, and the first B-29 strike on the factory from a ditch at the periphery of the Mitsubishi works. The Doolittle Raiders actually hit the Mitsubishi factory, killing a number of workers.

- The Zero was introduced to the Japanese public by name only in 1944. That seems to indicate that the Navy had different ideas about public relations than the Army, considering that the latter had apparently started even before Pearl Harbour to give its types glamorous names such as "Hayabusa". (At least, that's what I dimly remember reading somewhere ... I really don't know anything about the history of Japanese wartime propaganda.)

So much for my first impressions. I was amazed how much new (to me) information there was in a thin book like this that was published close to 50 years ago.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

P. S.:

*In order to provide the source on the Me 109 history aspect, here links to the interview, published in the German news magazine "Der Spiegel" in 1964:

Original German: hxxp://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-46162688.html

Googe Translate to English: hxxp://translate.google.com/translate?sl=de&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.spiegel.de%2Fspiegel%2Fprint%2Fd-46162688.html

In this interview, Messerschmitt describes that he asked for, and was given, pretty much freedom with regards to the Luftwaffe's stated requirements, after he had declared that these requirements would not permit building a fighter that was fast enough to catch a high-speed bomber.

I recently finished reading "Eagles of Mitsubishi" by Jiro Horikoshi.

Quite a well-written and informative book in my opinion!

Some observations:

- Horikoshi gives an overview over the requirements of the specifications for the 12-shi fighter. While he states that there were "nearly twenty items", he lists only 10. The translator muddies the waters by providing a foot note on range, which is not listed by Horikoshi, without clearly stating that this was part of the specifications. Of course, I'd have very much preferred to see a complete list of the specifications Horikoshi had to try and fulfill.

- Horikoshi considers the elliptical wing used on the A5M conventional and makes it clear that it was a deliberate design decision to give the A6M a different wing planform. Considering just how great an achievement the elliptical planform is usually considered to have been on the Spitfire, I'd have been very interested in his motivation for that change, but it's not mentioned.

- Horikoshi stresses the great advantage of wash-out on the A6M's outer wings and seems to consider it something of a novelty. Since wash-out was a well-established design technique even in WW1, I suspect that there must be more behind it than the book managed to convey (to me, at least

- In Mikesh's book on the A6M, there is a description of the aileron balance tabs reversing their function depending on the position of the flap selector. This is something also pointed out in John Deakin's report on flying the Confederate Air Force's restored Zero. Though the balance tabs get a lot of room in the book, probably because they lead to a fatal accident of one of the prototypes, this (to my limited knowledge, unique) feature is not mentioned, unfortunately.

- Horikoshi explains (in very broad terms) the methods used to achieve the required G load limit. I had read online that he wasn't happy with the safety factor of 1.8 and designed the Zero to 1.5 instead, but after reading his book, I would say that is a misunderstanding as he merely changed the way the strength of thin members in compression was calculated to allow for their greater range of reversible distortion. The safety factor actually achieved on the Zero apparently was just a shade under 1.8 G.

- The discussion of the elevator control system that avoided excessive authority at high speeds by the deliberate introduction of elasticity in the control circuit was quite interesting. To my surprise, this was actually picked up on by the US evaluators and described in a wartime NACA Memorandum authored by H. W. Phillips. I don't know why I've never heard about this before, as it's perfectly foot-noted in Horikoshi's book. The report, along with a more complete one on the combat-relevant characteristics of the A6M, can be found on the NACA's wiki page on Phillips: https://crgis.ndc.nasa.gov/historic/William_Hewitt_Phillips

- Horikoshi explains that they were using a 1:8 model in Mitsubishi's wind tunnel for developing the A6M. He doesn't mention the origin and the characteristics of the airfoil he chose for the A6M, the Mitsubishi 118, but I suppose it was probably also based on work done by Mitsubishi in the same wind tunnel. That's something I'd have liked to read more about.

- The A6M's design history has quite an interesting parallel to the development of the Me 109*, in a way: Willy Messerschmitt was unhappy with the Luftwaffe's specifications and expressed his concerns at the RLM, receiving permission to exceed the specified wing loading (at the expense of manoeuvrability, obviously) in his design. (The motivation was that the fighter, designed as specified, in Messerschmitt's opinion would have been unable to catch the high-speed bombers that were under development at the time.) Likewise, Jiro Horikoshi reached a point in the design process when he considered it impossible to fulfill all requirements, and at a meeting with the Navy asked if one or possibly two of the requirements could be dropped. It seems that suggestion was seriously considered, but then rejected.

- Horikoshi mentions the conflict between requirements for speed and for manoeuvrability. There was actually one meeting with the Navy in which Lt. Comdr. Minoru Genda (apparently representing the voice of the front line fighter pilots) and Lt. Comdr. Takeo Shibata (of the "fighter specialist group") hotly debated the question of manoeuvrability vs. performance. Genda, based on the success of the A5M in China, ranked manoeuvrability higher. Shibata favoured speed and range, arguing that skill could overcome manoevrability limitations, but no amount of skill could make the plane go faster or fly farther than its maximum range.

- There was actually a moment in which the Navy wavered in its otherwise cast-iron determination to have all requirements met, and that lead to Horikoshi calculating an alternative design for the A6M which featured a shorter range, a reduced aramement of only two 7.7 mm machine guns, and a smaller wing, in order to give the type better suitability for the "interceptor" role.

- The reason Horikoshi gives for the engine choice was a bit surprising to me, as he considered the opinion of the fighter pilots to be the decisive factor, and though they would not agree to a larger aircraft. Accordingly, he chose the slightly smaller and less powerful Nakajima Sakae radial over the higher-powered Mitsubishi Kinsei, actually feeling justified in his decision based on the initial comments the fighter pilots made when inspecting the mock-up for the first time. As (if I remember it correctly) as early as 1943 the Navy requested the design of an A6M variant with the Kinsei to improve the Zero's performance, I'm not sure that the original choice was indeed as obviously correct as Horikoshi thinks.

- The book contains a lot of clues to the limitations of the Japanese industry at the time, including a description of how the aircraft produced by Mitsubishi were delivered to the somewhat distant airfield they could take-off from by way of ox cart. How narrow the industrial base was for me was quite striking, considering that Mitsubishi as one of the two leading aircraft manufacturers was unable to pursue even two out of the three tasks of converting the A6M to the Kinsei, developing the succssor A7M, and developing the land-based J2M at the same time. Germany had engineering man-power shortages too, but the Japanese situation seems to have been even more serious. At least, that's my uninformed impression!

- Trivia: Horikoshi witnessed the Doolittle Raid from the design bureau office, and the first B-29 strike on the factory from a ditch at the periphery of the Mitsubishi works. The Doolittle Raiders actually hit the Mitsubishi factory, killing a number of workers.

- The Zero was introduced to the Japanese public by name only in 1944. That seems to indicate that the Navy had different ideas about public relations than the Army, considering that the latter had apparently started even before Pearl Harbour to give its types glamorous names such as "Hayabusa". (At least, that's what I dimly remember reading somewhere ... I really don't know anything about the history of Japanese wartime propaganda.)

So much for my first impressions. I was amazed how much new (to me) information there was in a thin book like this that was published close to 50 years ago.

Regards,

Henning (HoHun)

P. S.:

*In order to provide the source on the Me 109 history aspect, here links to the interview, published in the German news magazine "Der Spiegel" in 1964:

Original German: hxxp://www.spiegel.de/spiegel/print/d-46162688.html

Googe Translate to English: hxxp://translate.google.com/translate?sl=de&tl=en&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.spiegel.de%2Fspiegel%2Fprint%2Fd-46162688.html

In this interview, Messerschmitt describes that he asked for, and was given, pretty much freedom with regards to the Luftwaffe's stated requirements, after he had declared that these requirements would not permit building a fighter that was fast enough to catch a high-speed bomber.

Last edited: