I would tend to disagree with most of this.

I agree that the RLM mostly ran a neutrally-minded and reasonably effective bureaucratic process. But that means that we must look elsewhere to explain the great waste of effort. I do not see any such explanation in your reply.

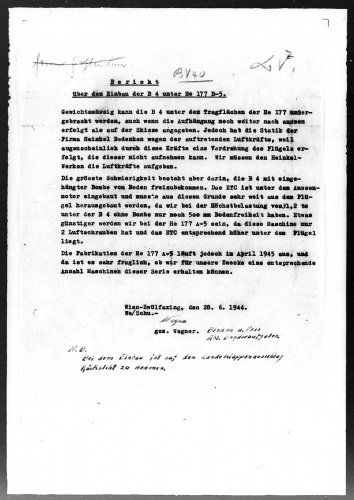

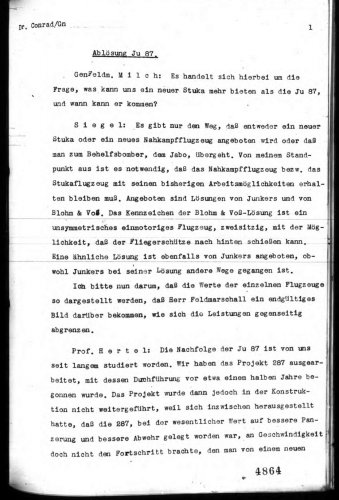

History invariably teaches us to look to the politicians. The senior Nazi figures did indeed indulge in power struggles and personal favouritism. The Volksjäger is just the best known aviation example, where design authority was granted to Heinkel despite widespread recognition of the Salamander's flaws. Another one was Hitler's diversion of the Me 262 fighter to "stuka" duties. The tale of the Ju 87 replacement is a particularly sorry one, of endless cancelled projects leading to an increasingly severe lack of capability as the war progressed. Hitler had even personally given the go-ahead to the BV 237, only to have it tied up in red tape and cancelled behind his back by those who favoured other manufacturers. The eventual diversion of the Schwalbe from its fighter role had not been the only interim expedient forced upon the Luftwaffe, though it was the last and most incongruous.

One has to bear in mind that this kind of infighting among one's bosses is not the kind of thing that diligent committee members record if they value their careers in a totalitarian society. The vast body of their output will be carefully turgid, just as you have found.

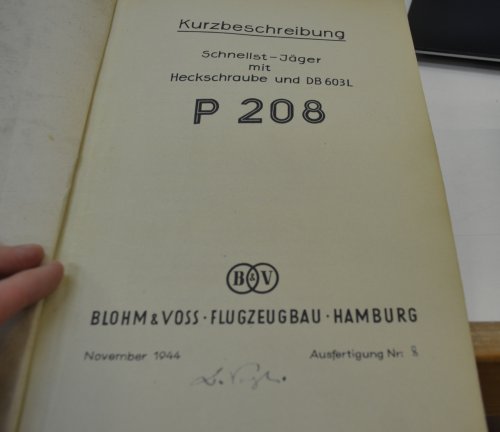

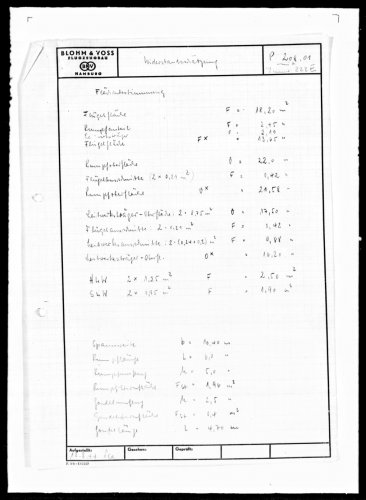

By marketing hype I mean the eternal optimism of technologists in the performance of their creations and in the time to delivery. The claims, visions and numbers embodied in the brochures and other submissions that they prepared for the RLM were invariably optimistic, often wildly so. Frankly, I see the technical role of these brochures as typically secondary, their main purpose was to pander to the perceived bias of the moment and to secure the next contract in the development chain.

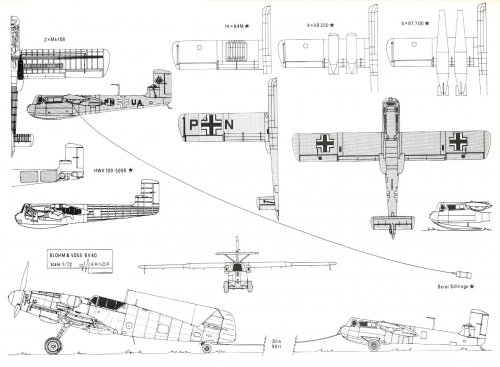

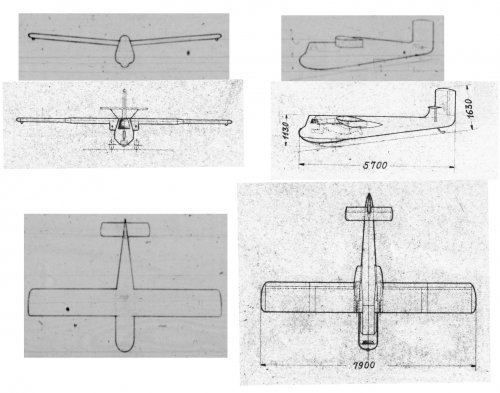

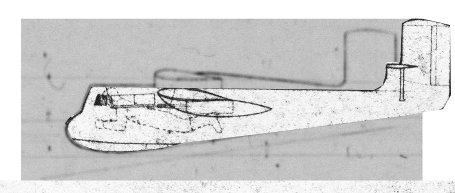

I do not collect images of them for that reason, as my interest is more directly in the design and engineering. But if you read some of the materials put out by Lippisch or B&V, they typically promote half-baked technologies such as tailless fighters, with absurdly short development times. "Deliveries could begin in eighteen months" might be a typical phrase accompanying a proposal that finally flew some three years later and proved far from combat-ready. For example the B&V P 208 piston-powered outboard-tail fighter was touted as a viable interim solution during the development of the jet engine. Three years later, the jet-powered P 215 derivative was still undergoing constant changes to its empennage when the war ended. Meanwhile Northrop in the USA had graphically demonstrated with his XP-56 that providing acceptable handling for such beasties was not as easy as it looked. Back in 1914, the British Ministry of Supply had refused to allow Armstrong Whitworth to develop the Dunne D.12 for this very reason, acknowledged by Dunne himself. Lippisch spent twenty years on the development trail that led from his earliest monoplane structures to the Me 163 Komet. Richard Vogt at B&V would have been fully aware of the issues but, being an enthusiastic inventor sort of chap and needing to promote his project by hook or by crook, he could not resist that glossy wrapper of what I have described as marketing hype.

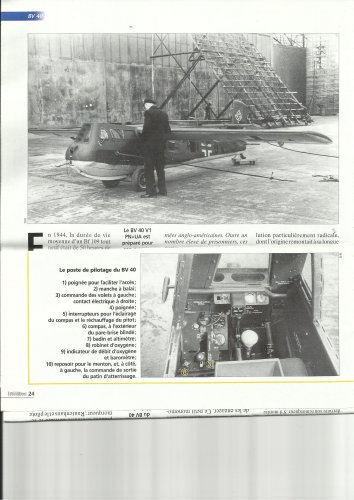

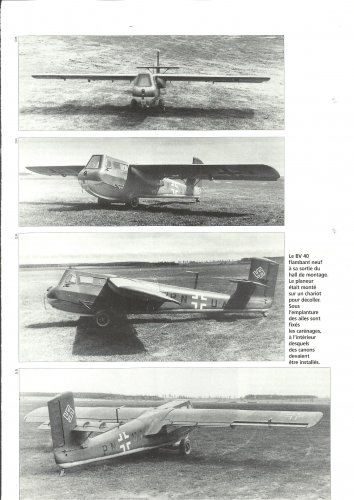

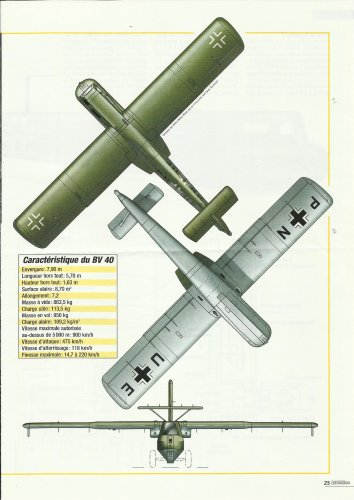

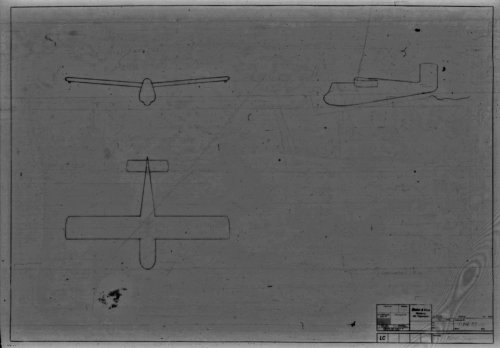

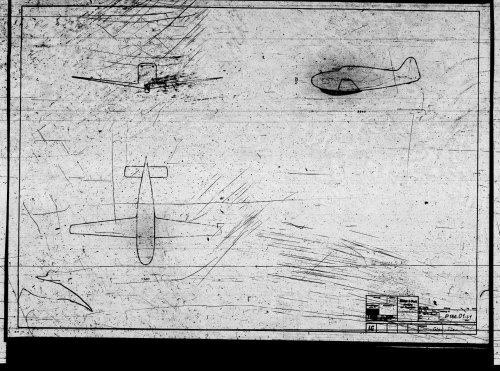

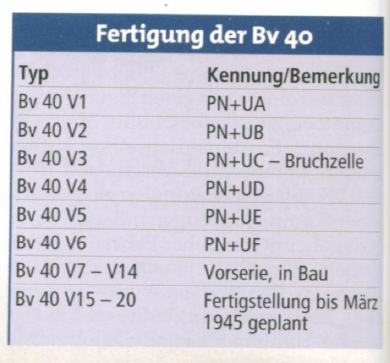

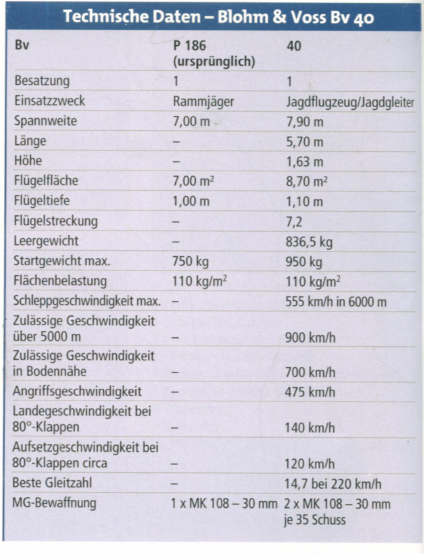

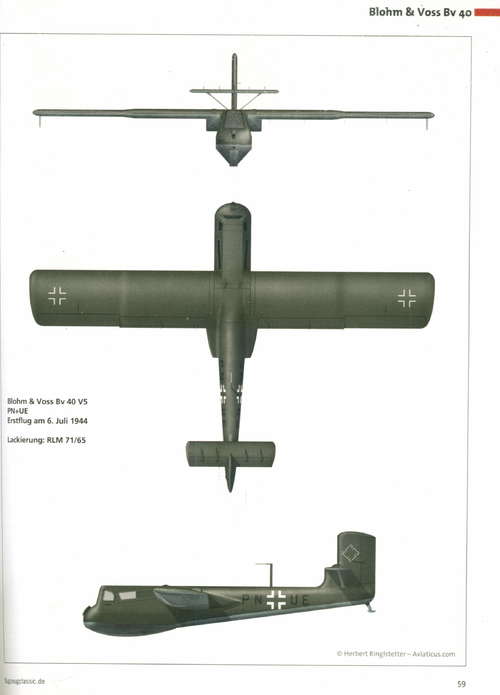

Returning to the BV 40, Pohlmann claims it was his boss Vogt's idea. I see it as just one of many zany ideas to be briefly investiagted by those with more practical air warfare experience before being dismissed. That it was taken to prototype stage and bounced around in various roles is more illustrative of the political realities over everybody's heads than any confidence in the concept. "Jawohl, Herr Senior Nazi, it is heavily armoured and flies at great speed, it will smash the American bombers!" "I shall increase the size of the labour camps at your disposal! Sieg heil!" kind of conversation. The company's aim has been achieved, though not through any sense of engineering or operational reality. (I am not suggesting that this was a specific gambit with the BV 40, it is meant only to be illustrative of the kind of thinking. And by the end of the war, there were at least two labour camps supplying B&V).

I think the important thing for a historian is to keep an open mind, not promote one's own theory beyond reason, and accept that others have probably gone down different rabbit-holes from one's own and found different bunnies at the bottom - all part of the same tangled warren.