The Allison XJ89 Turbojet

As the Cold War developed in the years after World War II, consensus among the U.S. Armed Forces emerged that the United States required a strategic bomber with intercontinental high-speed capability. In November 1955, Boeing and North American were awarded Air Force contracts to initiate preliminary design of what would become the Mach 3 XB-70 Valkyrie. Approximately six months later, Allison and General Electric were asked to submit engine proposals in support of the project.

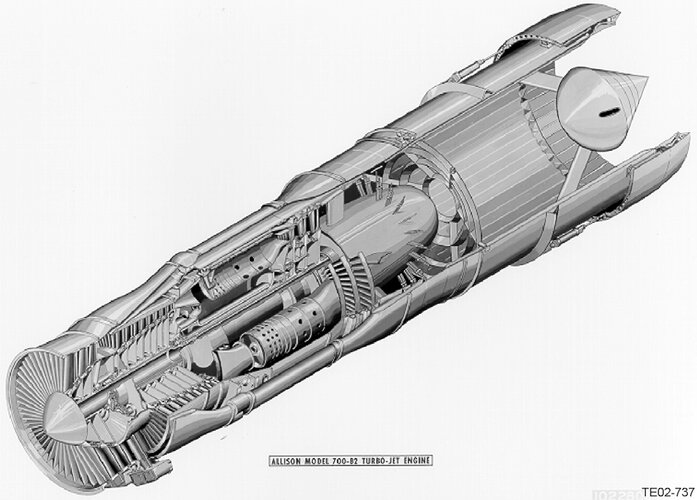

Allison’s response to the Air Force request was the Model 700-B2, which received the military designation XJ89-A-1. Although it was designated a turbojet, it was actually a low bypass turbofan.

The engine was Allison’s first twin-spool design, which featured a three-stage low pressure (LP) compressor, an eight-stage high pressure (HP) compressor, a single-stage LP turbine, a two-stage HP turbine, a high-altitude afterburner, and a variable-area plug-nozzle exhaust system. Air was carried from the outlet of the LP compressor around the HP compressor and reintroduced upstream of the afterburner. The controls and accessories were housed inside a cooled compartment to protect them from the temperatures resulting from high-Mach flight.

Maximum thrust was 34,500 lb at sea level. The engine was designed for Mach 2.8 at altitude with a Mach 3.0 objective. Maximum guaranteed altitude was 75,000 ft. The XJ89 was built and tested. Several variations were evaluated, including some with other design Mach numbers and others without an afterburner.

North American initially felt that the Allison XJ89 was “far better [than the GE offering] at high altitude and high Mach,”1 but GE improved its design in an attempt to narrow the gap. By April 1957, North American and Boeing announced that the two competing engines were virtually identical in projected performance and availability. On May 1, 1957, the Air Force declared GE the winner of the engine competition, thus terminating the XJ89 program.

AIAA 2002-3566

The Forgotten Allison Engines

D. T. Jensen and J. M. Leonard

Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, Allison Branch

Indianapolis, IN