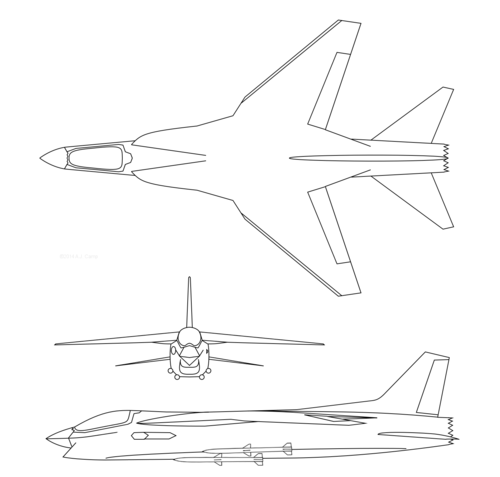

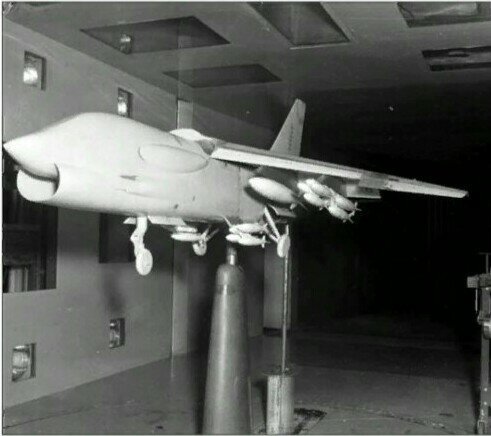

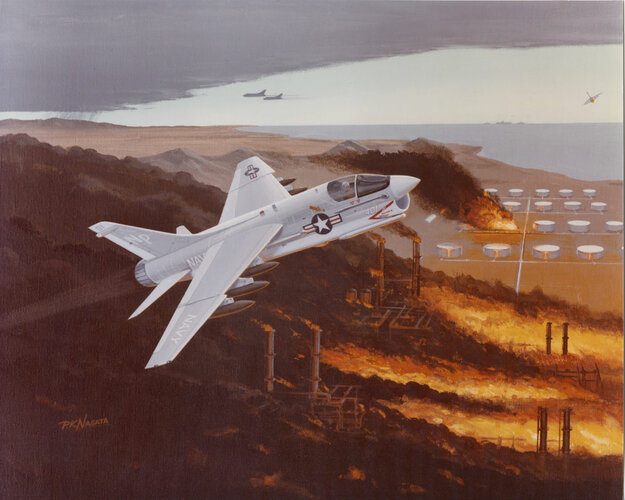

This is a "hodgepodge" of Google books Hearings and a few other tidbits, collected here and there. One can see that an afterburning / supersonic A-7D wasn't a far fetched prospect...

A-7D AIRCRAFT

Senator RUSSELL. On January 6, 1967, it was announced that the Air Force version of the A-7 aircraft would be equipped with an advanced version of a Rolls Royce Spey engine to be developed by the Allison Division of General Motors, and Rolls Royce, Ltd. Just why was it decided to use this new engine rather than the Pratt & Whitney engine used in the Navy version?

General CROW. During the course of studies to determine what was to be the final configuration of the Air Force version of the A-7 aircraft, it became evident that the Pratt & Whitney TF-30 engine used in the Navy version of the A-7 did not necessarily constitute an optimum choice for the Air Force A-7D. Takeoff thrust was inadequate and would require development of an afterburner installation, thereby introducing an added technical risk to the required production availability date. Coupled with this was the fact that proposed production availability of the TF-30 engine was already less than satisfactory. Moreover, Pratt & Whitney production capacity was becoming saturated, and additional facilities were said to be required in order to meet the added Air Force needs over and above Pratt & Whitney's existing military and commercial commitments. Overlying this was the fact that no more than two major engine producers constituted the major production base source for meeting urgent and expanding military requirements. From the standpoint of fostering a competitive environment, the situation was not encouraging.

Faced with this situation, the Air Force conducted a major reevaluation of the A-7 engine program. Proposals from Pratt & Whit

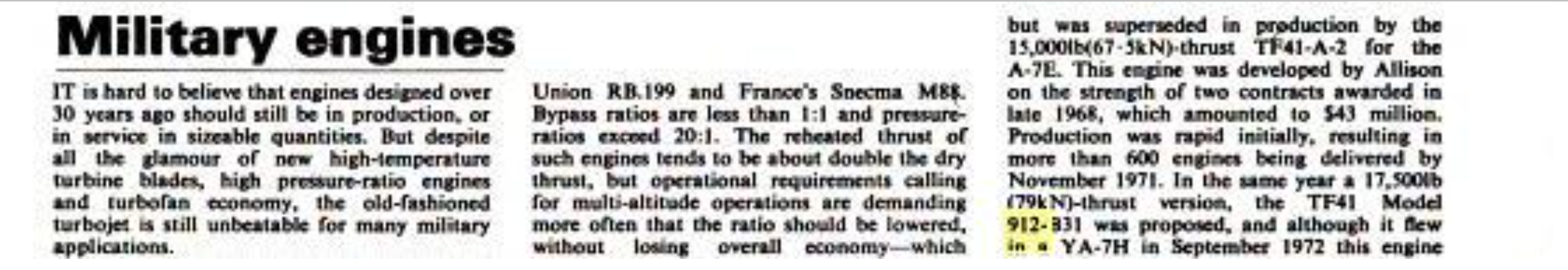

ney (TF-30-P-8 with afterburner) and Allison (Rolls Royce 912-B3 Spey) were subjected to comparative evaluation. Conclusions were that Spey performance was superior to that of the TF-30 (14,250 pounds of dry thrust for the Spey versus 10,950 pounds for the TF-30), while the technical risk was no greater. Spey production buildup could be achieved earlier, and at a greater monthly production rate, than could be achieved by Pratt & Whitney. Also, on a firm fixed price basis, the cost of a development and production program for 500 engines was estimated to be considerably cheaper for the Spey as compared to the TF-30. Allison, moreover, proposed a more competitive ceiling price and cost-sharing ratio than Pratt & Whitney.

The ultimate selection of the Spey engine (since designated the Ållison TF-41) to replace the TF-30 in the Air Force A-7D was a sound and logical decision. The Spey, now scheduled to fly in the A-7D in mid-1968, not only offers cost, delivery, and performance advantagesbut also provides us with a needed additional engine source.

Senator RUSSELL. Just what are the advantages of the Spey engine?

General CROW. The advantages of the Spey over the TF-30 are principally cost and availability.

Senator RUSSELL. How does the cost of the Spey engine compare with the cost of the Pratt & Whitney TF-30?

General CROW. The current Navy estimate for the unit cost of the TF-30-P-8 engine is $387,000. To this would have to be added the cost of afterburner (required to provide adequate takeoff performance for ground-based operation of the A-7D), which is estimated at $50,000 to $70,000-for an adjusted unit cost of $437,000 to $457,000 for the TF-30. This compares to a fixed-price contract unit cost of $342,904 for the Allison TF-41 (Spey).

Senator RUSSELL. What effect will the decision to change engines have on the availability of this aircraft to the combat forces?

General CROW. It will improve the availability of the A-7D to the combat forces. Initial deliveries will be earlier, the production acceleration to peak rate will be faster, and the peak rate will be higher.

Senator RUSSELL. What aircraft now being used in Southeast Asia will be replaced with the A-7D?

General CROW. The A-7D was programed to complement existing forces in the close air support and interdiction roles. It is scheduled to eventually phase into units now equipped with the F-100 and F-105 aircraft.

Senator RUSSELL. I noted a recent article indicating the Navy was having some problems with its version of the aircraft in which specific reference was made to steam ingestion into the engine and consequent reduction of power while being catapulted; loss of power or flameout in rainstorms; a noisy cockpit; and increasing costs. Are these problems limited to the Navy version?

General CROW. The technical problems concerning the engine are peculiar to the Pratt and Whitney TF-30 used in the Navy version. The cockpit noise problem is also applicable to the Air Force version. Engineering efforts to reduce or eliminate this difficulty are well underway. All increased costs on the Navy version are not necessarily applicable to the Air Force version. Certain increases are peculiar to the Navy configuration. At the same time, however, cost increases within the common airframe portion of the configuration are inevitably reflected in the cost of the Air Force airplane.

There being two sides to every coin, there are those in the Air Force who are not happy with the A-7D. This attitude stems primarily from the plane's being subsonic— in the Mach 0.9 class. Some in USAF would have preferred a supersonic aircraft. Indeed, the A-7D is the first turbojet fighter-type aircraft to enter Air Force service in more than fifteen years which has not been supersonic.

Although the Navy plans to operate the subsonic A-7 over North Vietnam on strike interdiction missions, Air Force philosophy calls for using supersonic fighter-bombers such as the F-105 Thunderchief and F-4 Phantom over the North. In the Air Force inventory the A-7 will replace the venerable F-100 Supersabre, the oldest of the Air Force supersonic fighter-bombers.

The A-7A/A-7B Corsairs in Navy use are launched on combat missions from aircraft carriers that can accelerate fully loaded aircraft to flying speeds with a 250-foot steam catapult. The TF30 engines in the 11,000- to 12,000-pound-thrust range are considered insufficient for runway takeoffs of combatloaded aircraft in the Southeast Asian environment. An obvious solution was to add an afterburner, but this would add weight to the aircraft at its after extremity, an unfavorable aerodynamic feature, and would give off "hot" exhaust, making the aircraft more vulnerable to infrared detection and heat-seeking missiles.

Accordingly, the Air Force decided to power its A-7D variant with the TF41-A-1 Spey turbofan engine, being developed and manufactured jointly by Rolls-Royce Ltd., of England, and the Allison Division of General Motors. The A-7D engines are being assembled in the US with some components being produced in Britain. The TF41 was rated at approximately 14,500 pounds maximum thrust. Tests to date indicate that the engine will develop about 500 pounds more thrust than had been estimated earlier, a very welcome bonus. (The first two A-7Ds off the production line this month will have Navy TF30-P-8 engines; subsequent A-7Ds will have the TF41 Spey.)

The major change in aircraft design was the adoption of a fixed wing for the A-7 in place of the variable-incidence wing of the F-8 Crusader fighter. The latter's wing rests flush with the top of the fuselage to provide a low angle of attack for high-speed and cruise flight. For landings and takeoffs the F-8 wing pivots upward to increase its angle of attack, in effect lowering the fuselage to provide the pilot with a good view of the flight deck or runway. The plane's ailerons, a section of the flaps, and the wing leading edges all droop simultaneously with the increase in wing incidence to further increase the effective camber to facilitate landing. Other airframe changes in the redesign of the F-8 to the A-7 configuration included reduction in size (partially made possible by not having an afterburner in the Corsair), a slightly reduced wing sweepback, and the addition of outboard ailerons.

These airframe changes have drawn criticism from opponents of the A-7, who claim that the A-7 provides for current avionics, weapons delivery, and powerplant technology to be installed in an airframe reflecting the state of the art in the early 1950s when the F-8 was designed. These critics contend that for a relatively small expenditure, especially in view of the number of aircraft contemplated, an airframe capable of Mach 1+ speeds could be designed-employing pivoting or variable-sweep wings-with all other A-7 capabilities. The question of cost is subjective, and debate on cost and relative survivability of supersonic versus subsonic light attack aircraft appears to have no end.