Payen Fighters

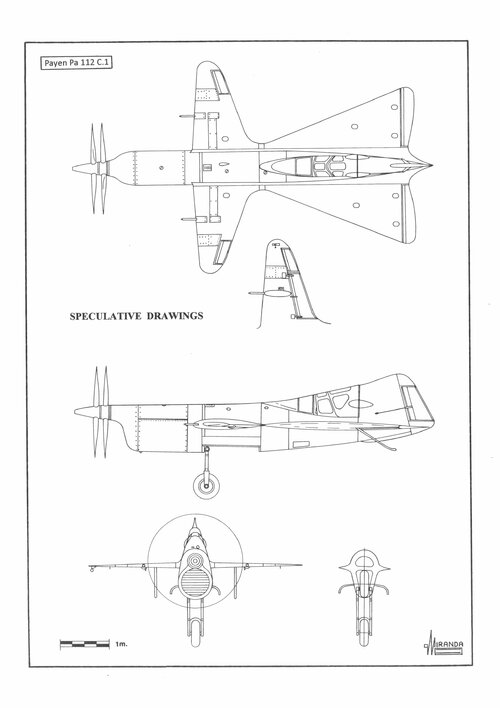

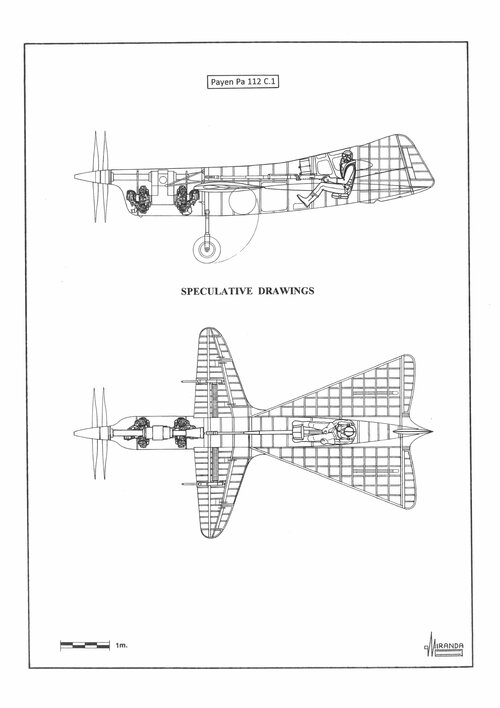

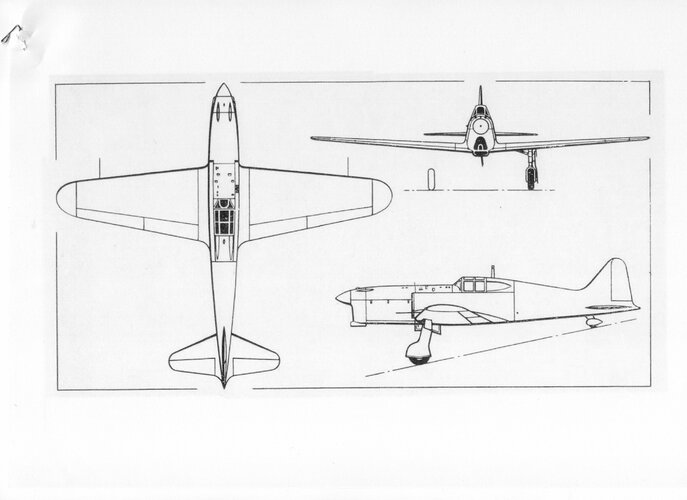

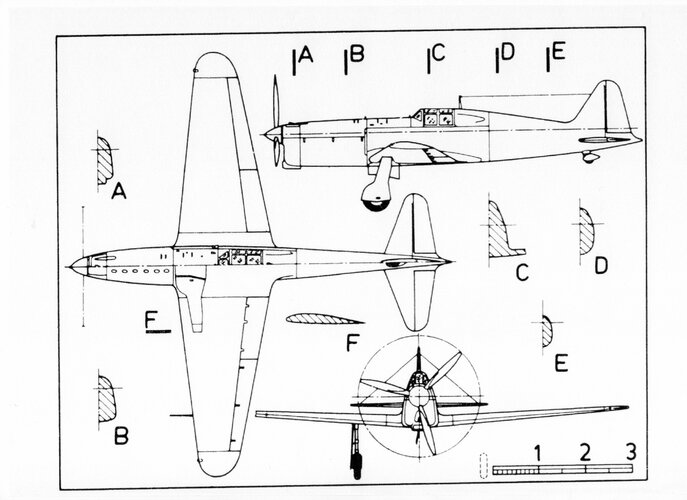

Between 1932 and 1942, Nicolas Payen designed a series of wooden canard-delta airplanes with a radical tandem-wing configuration.

In 1933 he built the Pa 100

Flèche Volante with small wings called

machutes and a 67 degree swept delta tailplane, to compete in the 3rd Coupe Deutsch. The

machutes had mobile wingtips which acted as ailerons and electrically-operated metallic flaps. The landing gear consisted of one centreline main leg, retracting backwards, and two outrigger auxiliary wheels retracting into the tailplane.

The engine should have been one 180 hp

Regnier R6, six-cylinder straight air-cooled, driving a fixed pitch wooden airscrew. But it was not possible to get one in time to participate in the competition and Payen had to adapt his project to the only engine available: one 380 hp Gnôme-Rhône 7Kd

Titan Major seven-cylinder radial air-cooled, weighting 270 Kg, totally unsuited for a racing aircraft. It was necessary to install a fixed undercarriage in more advanced position, to compensate the extra weight, and a tail skid. The wingtips ailerons were also changed by others, safer and of conventional type.

The refurbished plane was named Pa 101

Avion-Flèche, had 4.26 m wingspan, 5.75 m length, 2.2 m height, 6.86 sq.m wing surface, 750 kg maximum weight and one estimated maximum speed of 400 kph. It flew for the first time on 17 April 1935, being damaged in an accident just eight days later.

The Pa 101 airframe served as the basis for a new racer project, called Pa 110 CD (Coupe Deutsch). Designed in 1935, it differed from the previous model by its conventional landing gear, retracting backwards into the fuselage sides. It was hoped that it might be able to fly at 490 kph powered by one 200-240 hp Hirth 508D, eight-cylinder inverted-Vee, air-cooled engine, but the project was cancelled due to lack of funding.

When the Spanish Civil War began, the Republican Government had great difficulties in acquiring combat airplanes abroad, due to the international blockade. In the summer of 1936 Nicolas Payen offered the Spanish communists to build the Pa 110 C.1, the military version of the racer, through the Luxembourgian banker Rosenthal.

The power system designed for the fighter was made up of two 220 hp Renault 6Q-01, six-cylinder straight air-cooled engines installed in tandem face-to-face. Both engines were connected to the contra-rotating propellers power shaft by means of a Cotal-Baudot gearbox that allowed to electrically disconnect any of the engines by means of a clutch.

It was going to have an armament of two 7.5 mm Darne machine guns installed under the

machutes and one 20 mm H.S. 9 cannon, firing through the propellers hub, but the French Government had banned its export to Spain and had to be replaced by one 23 mm Danish Madsen cannon. The Pa 110 C.1 would have an estimated maximum speed of 460 kph, flying with one engine, and 550 kph with both engines. The estimated range was of 850 km.

The arrival of the Soviet fighters Polikarpov to Spain in October meant the cancellation of the project, which was redesigned as Pa 112 C.1 to adapt it to the

Chasseur Monoplace C.1 specification published by the

Ministère de l'Air on 3 June 1937.

The Renault 6Q were replaced by two 200-205 hp Salmson 9ND nine-cylinder radial air-cooled (surplus) engines commonly used by the Bloch M.B.81 of the

l’Armée de l’Air and by the Besson B. 411 of the

l’Aéronavale. Proposed armament was either a 20 mm H.S. 9 or an Oerlikon FFS cannon and two 7.5 mm MAC 34 M39 belt-feed machine guns installed in the interior of the

machutes, or two MAC 34A drum-feed installed under the

machutes.

A mock-up using the airframe of the Pa 101 was built in 1938. After being examined by technicians of the

l’Armée de l’Air, the project was rejected at the beginning of 1939, because of the great complexity of the power system. Payen offered to build the Pa 300 instead, a fighter capable to surpass the 520 kph of the

Programme Technique A23 if they provided him with an H.S.12 Y-45 engine. But the military, who had done most of his career flying in biplanes, found the

flèche aerodynamic solution to be too radical and preferred to build the Arsenal VG 33.

To fight these prejudices, Payen built the technological demonstrator Pa 22/2

Fléchair, which was captured by the Germans in 1940 while performing aerodynamic tests in the O.N.E.R.A. wind-tunnel of Chalais-Meudon. Under the new administration, the prototype was modified with the installation of a 180 hp

Regnier R6B-01 engine and a new open cockpit with the windscreen of one Arsenal VG 33. It made his first flight on 18 October 1941 and was destroyed during an Allied bombing in April 1944.

The

Phoney War ended with the invasion of Belgium and the Netherlands and the German attack against France, using 860 fighters Bf 109E, three-hundred-and-fifty Bf 110, 1,120 medium bombers, 342 dive bombers and 591 reconnaissance airplanes.

L'Armée de l'Air had only thirty-seven Bloch M.B.151, ninety-three Bloch M.B.152, ninety-eight Curtiss H.75A, two-hundred-and-seventy-eight Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 and sixty-seven Potez 631 fighters

bons de guerre, supported by thirty Gloster Gladiators and forty-eight Hurricanes British fighters. During the Battle of France 1,279 German, 872 French and 944 British airplanes were destroyed by different causes.

One of the main reasons for the success of the

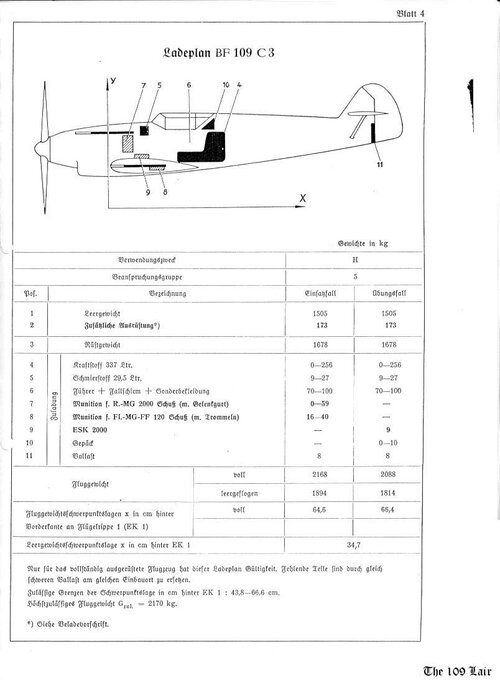

Blitzkrieg against the French and British Armies, in May 1940, was the aerial superiority obtained when the Messerschmitt Bf 109 E-3 entered service with the Luftwaffe. It happened at the right time, when the main French fighter Morane-Saulnier M.S.406 was replaced by the second generation fighters Dewoitine D.520 and Arsenal VG 33. During the

Phoney War,

l’Armée de l’Air tried to fill the gap with the Bloch M.B.152 and Curtiss H.75A fighters, helped by the British Hawker Hurricane Mk.I. But the Messerschmitt would prove superior.

This seems to be the origin of the commonly accepted paradigm about the assumed inferiority of the French technology. It is not common knowledge that France already had operational naval radar in 1934. And that, at the beginning of June 1940, the antiaircraft artillery defending Paris was controlled by the most advanced radar in the world, able to operate in wavelengths from 80 to 16 cm against the 3.5 to 1.5 m of the British or the 2.4 m to 53 cm of the German radar.

The French scientists were also ahead of their German equivalents in the field of nuclear fission. By early 1940, the CNRS controlled the highest reserve in the world of uranium (8 tons coming from the Belgian Congo) and 200 kg of heavy water from the Norwegian enterprise

Norsk Hydro.

The French tanks of 1940 had better armour and armament than the Germans. The

Marine Française (the French combat fleet) was superior to the

Kriegsmarine in firepower with the

Béarn carrier and six squadrons of Loire Nieuport L.N.401/411 dive bombers that technically surpassed the German Ju 87.

The destructiveness of the air-to-air weapons installed in the French fighters was slightly higher that their German equivalents, although the quality of the aiming devices OPL 31, RX 39 and GH 38 used by

l’Armée de l’Air was somehow inferior to the Zeiss

Revi C/12 reflector gunsight of the Luftwaffe. The following text compares the armament used by the French and German fighters during the Battle of France