You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

DHC-4 Caribou, Projects & Variants

- Thread starter hesham

- Start date

Nice find.

regards,

Greg

regards,

Greg

- Joined

- 13 June 2007

- Messages

- 2,172

- Reaction score

- 3,075

Greetings All -

The local hobby shop gave me a bunch of late '50s/early '60s Air Progress magazines. The 1957/58 Annual has the attached image with a caption about the US Army making an off the drawing board purchase of 5 for evaluation purposes. The tail feathers obviously made a significant change before first flight....

Enjoy the Day! Mark

The local hobby shop gave me a bunch of late '50s/early '60s Air Progress magazines. The 1957/58 Annual has the attached image with a caption about the US Army making an off the drawing board purchase of 5 for evaluation purposes. The tail feathers obviously made a significant change before first flight....

Enjoy the Day! Mark

Attachments

Interesting find - any further information?

Regards,

Greg

Regards,

Greg

- Joined

- 25 July 2007

- Messages

- 4,299

- Reaction score

- 4,187

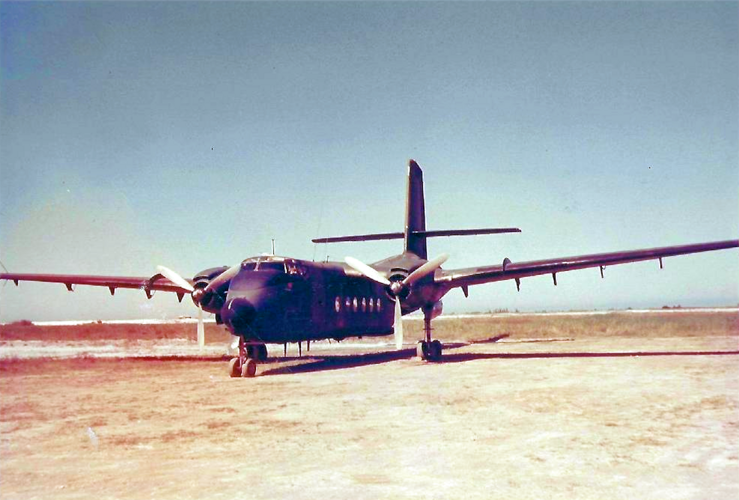

In the 1954 concept, the DHC-4 tail looked rather like a squat version of the DHC-3 tail. Attached is a poor quality scan (sorry, source now forgotten) of a later DHC-4 model being tested.

The original caption claimed that this was testing a "flattened V-tail". It seems more likely that deHavilland was testing the twin-tailed configuration in Mark's 3-view but without the endplates fitted.

BTW: on Caribou tails, for a while, the short-nosed prototype CF-KTK-X carried a dorsal fin (up to just in front of the horizontal tails).

The original caption claimed that this was testing a "flattened V-tail". It seems more likely that deHavilland was testing the twin-tailed configuration in Mark's 3-view but without the endplates fitted.

BTW: on Caribou tails, for a while, the short-nosed prototype CF-KTK-X carried a dorsal fin (up to just in front of the horizontal tails).

Attachments

- Joined

- 6 November 2010

- Messages

- 5,246

- Reaction score

- 5,473

From "Canadian Aircraft since 1909" by K.M. Molson & H.A. Taylor, Putnam, 1982.

Extensive model tests were made as the Caribou's fuselage had to be angled sharply upwards to give adequate truck loading clearance, and included a large-scale model tested in flight mounted above the Otter RCAF 3667.

The prototype, CF-KTK-X, was first flown on 30 July, 1958, at Downsview by George Neal and David Charles Fairbanks, with flight engineer H. Brinkman. It was found that to obtain the required range of centre of gravity movement, a 45 in (1.14m) section had to be inserted in the forward fuselage. All subsequent DHC 4s had this built in and the prototype was later modified. Also it was found that an oscillating vortex was created off the rounded edges of the rear fuselage, causing a slight weaving of the aircraft. Initially a dorsal fin was fitted but was not effective. Then strakes were added along the lower edges of the fuselage and these created a stable vortex and the weaving disappeared. It was the solving of this stability problem that resulted in the sharp lower fuselage corners of the DHC 4 development, the DHC-5.

[...]

An improved DHC 4A version was planned, with two General Electric J-85-GE-7 jet engines with adjustable nozzles, mounted in the rear fuselage as tested in the experimental STOL Otter which would give enhanced STOL capabilities. This version was not built as priority was given to the Caribou II which became the DHC-5 Buffalo. It was then planned to make a version of the DHC-5 with these jet engines installed but this was never done owing to the restrictions placed on the US Army for operating fixed wing aircraft.

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,815

- Reaction score

- 15,698

We must merge those two topics;

this one and that one;

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,13200.0.html

this one and that one;

http://www.secretprojects.co.uk/forum/index.php/topic,13200.0.html

Kiltonge

Greetings Earthling

- Joined

- 24 January 2013

- Messages

- 628

- Reaction score

- 1,177

Flight, 1957:

Which sadly it never did.

The DHC-4 was hobbled in the market by the fact that it couldn't haul much more payload than a cheap-as-stones C-47, much of this being due to the selection of the R-2000 engines which were out-bored R-1830s.

The STOL capability was awesome for those edge-cases that warranted it but for everyone else a Dak did the job for a tenth of the price ( about £25,000 for a decent reconditioned Dak in 1958 versus £150 - 200,000 for a DHC-4 ).

With a payload of some 9,000 lb the DHC-4 will have Pratt and Whitney

R-1830 or R-2000 engines at first, later changing to Dart, T55 or Gazelle

turboprops.

Which sadly it never did.

The DHC-4 was hobbled in the market by the fact that it couldn't haul much more payload than a cheap-as-stones C-47, much of this being due to the selection of the R-2000 engines which were out-bored R-1830s.

The STOL capability was awesome for those edge-cases that warranted it but for everyone else a Dak did the job for a tenth of the price ( about £25,000 for a decent reconditioned Dak in 1958 versus £150 - 200,000 for a DHC-4 ).

Was browsing through a run of a U.S. magazine titled Flight recently and came across an article in the April 1957 issue announcing the DHC-4 Caribou, but w/a drawing and 3-view showing twin tails. The 3-view is dated 21 January 1957, revised on 23 February 1957, and it gives the span of the tail as 37 feet. News to anyone?

Attachments

- Joined

- 26 May 2006

- Messages

- 34,815

- Reaction score

- 15,698

Clioman said:Yes, by all means - I hadn't thought to do a search before posting. Sorry 'bout that.

No problem Clioman,and nice find.

- Joined

- 21 May 2006

- Messages

- 2,993

- Reaction score

- 2,249

Info on 'experimental DHC-4 Caribou flight refueliling tanker'

G’day all

I just came across the following in relation to the De Havilland Canada DHC-4 Caribou:

Does anyone have any further information pertaining to this experimentation – dates, photos/drawings etc.....

Also, was it a US Army or De Havilland Canada experiment?

Regards

Pioneer

G’day all

I just came across the following in relation to the De Havilland Canada DHC-4 Caribou:

(Source: http://www.airvectors.net/avdhc4.html)“The US Army developed fuel bladders, in the form of rubber cylinders that looked like very fat tires, that could stow 1,326 liters (350 US gallons) each. Up to three could be hauled in the cargo bay, primarily to increase range for ferry flights, but also potentially for delivery of fuel to forward areas. There was also an experiment with using the Caribou as an inflight refueling tanker, but it appears this was never done operationally.”

Does anyone have any further information pertaining to this experimentation – dates, photos/drawings etc.....

Also, was it a US Army or De Havilland Canada experiment?

Regards

Pioneer

- Joined

- 9 October 2009

- Messages

- 21,928

- Reaction score

- 13,552

maxmwill

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 29 October 2011

- Messages

- 60

- Reaction score

- 21

Armed Caribou

As a wee lad, knee high to a grasshopper, I had an uncle(he passed recently) who would like to regale me with tales of his Army days. Not the kind that began with, "There I was, at 10,000 feet...........", but more like, "I liked the Caribou.", and then the tale would begin.

One of his stories of his life in a Caribou squadron(he never did tell me which one), was that one day, the guys decided to see if they could turn the 'Bou into a tactical transport, one that could soften up the airfield, if they are coming under fire. So, after mounting a couple pair of 50s up by the pilot(two on each side with a swivel stick so the pilot could strafe), there being hardpoints in the wings, proceeded to mount a missile(Tiny Tim, I think, although a cruel and heartless sadist named "Age" has caused that to emit haze) and some napalm tanks, and proceeded to demonstrate in front brass, which, unfortunately included a couple Air Force generals, who were none too pleased with this.

Over the years, I lost touch with my uncle until it was too late, and multiple internet searches have come up fruitless, so, any truth to that, or was it a beloved elder relative spinning tales to impress a nephew?

As a wee lad, knee high to a grasshopper, I had an uncle(he passed recently) who would like to regale me with tales of his Army days. Not the kind that began with, "There I was, at 10,000 feet...........", but more like, "I liked the Caribou.", and then the tale would begin.

One of his stories of his life in a Caribou squadron(he never did tell me which one), was that one day, the guys decided to see if they could turn the 'Bou into a tactical transport, one that could soften up the airfield, if they are coming under fire. So, after mounting a couple pair of 50s up by the pilot(two on each side with a swivel stick so the pilot could strafe), there being hardpoints in the wings, proceeded to mount a missile(Tiny Tim, I think, although a cruel and heartless sadist named "Age" has caused that to emit haze) and some napalm tanks, and proceeded to demonstrate in front brass, which, unfortunately included a couple Air Force generals, who were none too pleased with this.

Over the years, I lost touch with my uncle until it was too late, and multiple internet searches have come up fruitless, so, any truth to that, or was it a beloved elder relative spinning tales to impress a nephew?

For some basic info on Caribou turboprop conversion projects

- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,730

- Reaction score

- 6,068

RCV-2B Pathfinder, a one-of-a-kind "Boo"

Beginning in 1961, Army Security Agency soldiers operated in Vietnam, conducting reconnaissance and interception of Viet Cong radio transmissions. Since the ASA could not be officially present in Vietnam, the units bore the code name Radio Research (RR). As of April 1962, the ASA began using aircraft to directionalize the signal. After unsuccessful attempts with the H-19 helicopter, the choice fell upon the U-6 Beaver, followed by the U-8 Seminole. However, both of these types could only locate the radio signal. A single CV-2B Caribou [62-4147, c/n 82] was therefore modified by the U.S. Army in 1965 as the Pathfinder SIGINT/ELINT reconnaissance platform and designated RCV-2B, being the first aircraft whose crew both could intercept and record transmissions. The story of that one-of-a-kind aircraft would be all but forgotten were it not for the precious testimony left online by members of its crew.

Pathfinder's assignment

In January 1963, a month after its acceptance by the US Army, [62-4147] was transfered to the Army Security Agency (ASA) at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where it was modified (equipped with HF DF) and assigned to Pathfinder duties. Three years later, in January or February 1966 (depending on sources), the RCV-2B was assigned to the 3rd Radio Research Unit at Tan Son Nhut Airport, in Ho Chi Minh. With the increasing number of personnel and equipment, however, the ASA in Vietnam was reorganized in June 1966. For the aviation units, an entire aviation battalion, the 224th Aviation Battalion (Radio Research), was created, which had four companies: 138th Aviation Company (RR), at Da Nang; 144th Aviation Company (RR), at Nha Trang; 146th Aviation Company (RR), at Tan Son Nhut (where the RCV-2B operated from); and 156th Aviation Company (RR), at Can Tho. According to one crew member, however, Pathfinder did not fall under any unit in Vietnam and was directly subordinate to the US ASA Pacific headquarters. This could be explained by the fact that the aircraft operated throughout South Vietnam, while the 146th Aviation Co. (RR) was assigned to III.CTZ. Whatever the case, it certainly used the facilities of the 146th Aviation Co. (RR).

Configuration and specific equipment

Pathfinder's crew consisted of eight men - pilot, copilot, flight engineer, four ASA operators and a mission controller. Flights usually lasted 4 hours, after refueling they could stretch up to seven hours. "Pathfinder" operated throughout South Vietnam, occasionally flying beyond its borders to Cambodia, Laos or North Vietnam. There were four positions in the fuselage for operators who could record and intercept radio transmissions in the short and very short wave bands, or locate radio transmissions in the short wave band. There was also a teletypewriter on board for secure air-ground data communication. Since the equipment used up more electrical power, the two turbines of an electric generator were placed under the wings. An old World War II sight was mounted in the cabin floor to record the exact position on the ground. The enemy's position could also be verified using an infrared camera. The pilots had a Sperry C-12 compass system, a Doppler radar and a Decca navigation system at their disposal. This particular system was quite old (it ceased to be used in Vietnam in 1968), but its main purpose was to indicate the aircraft's position (which was important for determining the position of the focused radio signal) while actual navigation itself was only a secondary use. Finally, a Polaroid camera was carried on board for taking instant pictures of the pilot's instrument panel. The photos of the panel were then placed on a large map board with signal search.

A spectacular incident

A spectacular incident

On Sept. 20, while performing an intelligence intercept operation over North Vietnam, slightly north of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), at about 5,000 ft. altitude, Pathfinder started to take ground fire from an NVA gun emplacement situated on a 2,000 ft. mountain. A 37mm anti-aircraft hit the tail, while the belly of the airplane was peppered with .30cal. at extreme range. The pilot immediately banked towards the DMZ, being able to skillfully turn the plane without rudder function, compensating by alternating the prop pitch. He subsequently landed the crew safely without any combat injury on the PSP-runway at U.S. base Dong Ha, a few kilometers below the DMZ.

At Dong Ha everyone piled out and laid on the PSP, looking at the belly. Nothing had penetrated the skin, but the bottom of the aircraft looked like it was attacked by someone with a ball pen hammer (unfortunately, no photos of the belly were taken). Suddenly they noticed a group of Air Force people staring at the tail with their mouths hanging open, realizing only then the damage sustained. After a few nervous cigarettes, the pilot gave the crew the option of returning to Phu Bai in the Caribou, or riding in the SAR helicopter that would be escorting them. Each and every one of them chose to climb back in the Caribou for the return to Phu Bai. (A much more detailed account of the whole episode can be found in the second link below.)

After being repaired, Pathfinder was assigned to the 146th Aviation Co. (RR), but its career was short-lived — not because of this or any other accident, but by an agreement between the Army and the Air Force, whereby the Army pledged to hand over all medium transport aircraft to the Air Force while the USAF in return would limit the operation of helicopters. The agreement, under operation "Red Leaf", was to be fulfilled by the end of 1966. The handover, of course, also concerned the RCV-2B, which was to be transfered in "normal" configuration, i.e. as a regular transport machine. Its pilot, Capt. Dexter, was given the task of developing instructions on what needed to be done to return [62-4147] to a "normal" configuration. However, Dexter argued that the modifications were so extensive that they could not be removed in Vietnam. Besides, the Army wanted to use Pathfinder's capabilities as long as possible. This somewhat delayed the handover, but the RCV-2B, now a C-7A, was finally turned over to the USAF on May 31, 1967, and transfered in August to McClellan AFB (Air Force Logistics Command) in Sacramento, CA for repairs. Eventually, it returned to Vietnam, being assigned in 1968 to the 457th Squadron at Can Ranh Bay (Vietnam Tail code "KA"). After suffering a minor gear-up landing in 1971, the aircraft was transfered on March 31, 1972 to the 377th ABSWG/310th TAS at Phu Cat, then handed over to the South Vietnam Air Force's 427th Transport Squadron later that year, under the Military Assistance Program (Tail code "GD"). Nothing is known of its later whereabouts.

Redesignation

The question of the aircraft's redesignation after its transfer to the USAF is tricky. First of all, the notion that CV-2A aircraft became C-7A while CV-2Bs were redesignated as "C-7B" doesn't hold water when you take a close look at the detailed list of all Caribou aircraft and their individual histories. Indeed, the latest version of dhc4and5.org's so-called "Caribou Roster" (Revision #13) does not include a single "C-7B" aircraft! And so, if we are to believe that site's research (and they are the ultimate source on all DHC-4/DHC-5 aircraft, after all), absolutely every remaining Army Caribou, whether AC-1/CV-2A, or AC-1A/CV-2B, was redesignated in 1967 as a USAF C-7A (with the exception of the YAC-1 prototypes, which became YC-7A). Even the designation "VC-7A", supposed to have been used for several examples returned to the US Army National Guard, is apparently totally apocryphal!

Also, there are several sources alluding to the RCV-2B becoming the "RC-7B" but that too seems apocryphal

Compiled, translated and/or rewritten from the following sources:Pathfinder's assignment

In January 1963, a month after its acceptance by the US Army, [62-4147] was transfered to the Army Security Agency (ASA) at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, where it was modified (equipped with HF DF) and assigned to Pathfinder duties. Three years later, in January or February 1966 (depending on sources), the RCV-2B was assigned to the 3rd Radio Research Unit at Tan Son Nhut Airport, in Ho Chi Minh. With the increasing number of personnel and equipment, however, the ASA in Vietnam was reorganized in June 1966. For the aviation units, an entire aviation battalion, the 224th Aviation Battalion (Radio Research), was created, which had four companies: 138th Aviation Company (RR), at Da Nang; 144th Aviation Company (RR), at Nha Trang; 146th Aviation Company (RR), at Tan Son Nhut (where the RCV-2B operated from); and 156th Aviation Company (RR), at Can Tho. According to one crew member, however, Pathfinder did not fall under any unit in Vietnam and was directly subordinate to the US ASA Pacific headquarters. This could be explained by the fact that the aircraft operated throughout South Vietnam, while the 146th Aviation Co. (RR) was assigned to III.CTZ. Whatever the case, it certainly used the facilities of the 146th Aviation Co. (RR).

Configuration and specific equipment

Pathfinder's crew consisted of eight men - pilot, copilot, flight engineer, four ASA operators and a mission controller. Flights usually lasted 4 hours, after refueling they could stretch up to seven hours. "Pathfinder" operated throughout South Vietnam, occasionally flying beyond its borders to Cambodia, Laos or North Vietnam. There were four positions in the fuselage for operators who could record and intercept radio transmissions in the short and very short wave bands, or locate radio transmissions in the short wave band. There was also a teletypewriter on board for secure air-ground data communication. Since the equipment used up more electrical power, the two turbines of an electric generator were placed under the wings. An old World War II sight was mounted in the cabin floor to record the exact position on the ground. The enemy's position could also be verified using an infrared camera. The pilots had a Sperry C-12 compass system, a Doppler radar and a Decca navigation system at their disposal. This particular system was quite old (it ceased to be used in Vietnam in 1968), but its main purpose was to indicate the aircraft's position (which was important for determining the position of the focused radio signal) while actual navigation itself was only a secondary use. Finally, a Polaroid camera was carried on board for taking instant pictures of the pilot's instrument panel. The photos of the panel were then placed on a large map board with signal search.

A spectacular incident

A spectacular incidentOn Sept. 20, while performing an intelligence intercept operation over North Vietnam, slightly north of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), at about 5,000 ft. altitude, Pathfinder started to take ground fire from an NVA gun emplacement situated on a 2,000 ft. mountain. A 37mm anti-aircraft hit the tail, while the belly of the airplane was peppered with .30cal. at extreme range. The pilot immediately banked towards the DMZ, being able to skillfully turn the plane without rudder function, compensating by alternating the prop pitch. He subsequently landed the crew safely without any combat injury on the PSP-runway at U.S. base Dong Ha, a few kilometers below the DMZ.

At Dong Ha everyone piled out and laid on the PSP, looking at the belly. Nothing had penetrated the skin, but the bottom of the aircraft looked like it was attacked by someone with a ball pen hammer (unfortunately, no photos of the belly were taken). Suddenly they noticed a group of Air Force people staring at the tail with their mouths hanging open, realizing only then the damage sustained. After a few nervous cigarettes, the pilot gave the crew the option of returning to Phu Bai in the Caribou, or riding in the SAR helicopter that would be escorting them. Each and every one of them chose to climb back in the Caribou for the return to Phu Bai. (A much more detailed account of the whole episode can be found in the second link below.)

After being repaired, Pathfinder was assigned to the 146th Aviation Co. (RR), but its career was short-lived — not because of this or any other accident, but by an agreement between the Army and the Air Force, whereby the Army pledged to hand over all medium transport aircraft to the Air Force while the USAF in return would limit the operation of helicopters. The agreement, under operation "Red Leaf", was to be fulfilled by the end of 1966. The handover, of course, also concerned the RCV-2B, which was to be transfered in "normal" configuration, i.e. as a regular transport machine. Its pilot, Capt. Dexter, was given the task of developing instructions on what needed to be done to return [62-4147] to a "normal" configuration. However, Dexter argued that the modifications were so extensive that they could not be removed in Vietnam. Besides, the Army wanted to use Pathfinder's capabilities as long as possible. This somewhat delayed the handover, but the RCV-2B, now a C-7A, was finally turned over to the USAF on May 31, 1967, and transfered in August to McClellan AFB (Air Force Logistics Command) in Sacramento, CA for repairs. Eventually, it returned to Vietnam, being assigned in 1968 to the 457th Squadron at Can Ranh Bay (Vietnam Tail code "KA"). After suffering a minor gear-up landing in 1971, the aircraft was transfered on March 31, 1972 to the 377th ABSWG/310th TAS at Phu Cat, then handed over to the South Vietnam Air Force's 427th Transport Squadron later that year, under the Military Assistance Program (Tail code "GD"). Nothing is known of its later whereabouts.

Redesignation

The question of the aircraft's redesignation after its transfer to the USAF is tricky. First of all, the notion that CV-2A aircraft became C-7A while CV-2Bs were redesignated as "C-7B" doesn't hold water when you take a close look at the detailed list of all Caribou aircraft and their individual histories. Indeed, the latest version of dhc4and5.org's so-called "Caribou Roster" (Revision #13) does not include a single "C-7B" aircraft! And so, if we are to believe that site's research (and they are the ultimate source on all DHC-4/DHC-5 aircraft, after all), absolutely every remaining Army Caribou, whether AC-1/CV-2A, or AC-1A/CV-2B, was redesignated in 1967 as a USAF C-7A (with the exception of the YAC-1 prototypes, which became YC-7A). Even the designation "VC-7A", supposed to have been used for several examples returned to the US Army National Guard, is apparently totally apocryphal!

Also, there are several sources alluding to the RCV-2B becoming the "RC-7B" but that too seems apocryphal

1. Being eventually returned to transport status, [62-4147] just became a C-7A like any other. And even if it had been temporarily designated with an "R" modifier until the changes could be made (there was no "E" modifier yet), surely it would have been an "RC-7A" not a "B"... but even that designation can't be found anywhere! All of this shows the importance of always checking the facts instead of repeating age-old mistakes, even when the seem to emanate from serious sources.1 When the DoD finally allocated RC-7B, 40 years later, for another De Havilland Canada aircraft (the DHC-7 Crazy Hawk), it caused quite a stir among designation buffs because it made little sense to give the four-engine DHC-7 the same designation as the earlier, twin-engine DHC-4 (someone must have realized it was not quite right, and Crazy Hawk became the EO-5C on August 15, 2004).

- http://www.aviastar.org/air/canada/dehavilland_caribou.php

- http://www.dhc4and5.org/SEMA.html

- https://www.airhistory.net/photo/420373/62-4147/24147

- https://www.nam-valka.cz/letadla/rc-7.html

Attached below are pictures of the Pathfinder, its crew, the battle damage, and the "wounded heart" painted by the Crew Chief to indicate battle damage, most from the Robert Cumming and Kenneth E. McNamara collections.

Attachments

-

rcv2.jpg54.3 KB · Views: 22

rcv2.jpg54.3 KB · Views: 22 -

pfdr.jpg28.9 KB · Views: 21

pfdr.jpg28.9 KB · Views: 21 -

Pathfindertail.jpg67.3 KB · Views: 19

Pathfindertail.jpg67.3 KB · Views: 19 -

pathfind.jpg28 KB · Views: 20

pathfind.jpg28 KB · Views: 20 -

C3444.jpg74.2 KB · Views: 18

C3444.jpg74.2 KB · Views: 18 -

C3443.jpg93.5 KB · Views: 21

C3443.jpg93.5 KB · Views: 21 -

C3304.jpg48.2 KB · Views: 22

C3304.jpg48.2 KB · Views: 22 -

C3303.jpg130.3 KB · Views: 22

C3303.jpg130.3 KB · Views: 22 -

C3302.jpg100.8 KB · Views: 21

C3302.jpg100.8 KB · Views: 21 -

C3301.jpg65.2 KB · Views: 19

C3301.jpg65.2 KB · Views: 19 -

1740747211683.png899.4 KB · Views: 26

1740747211683.png899.4 KB · Views: 26

Last edited:

Atomic Coyote

I really should change my personal text

- Joined

- 31 March 2015

- Messages

- 30

- Reaction score

- 48

A while back I remember a company in New Jersey was re-engining them with PT-6s; http://www.dhc4and5.org/Turbo.html

Apparently it's proceeding very slowly, but I think most of these have been there since I last visited that airport in the late 2000s.

Apparently it's proceeding very slowly, but I think most of these have been there since I last visited that airport in the late 2000s.

Similar threads

-

-

-

Cessna T-37 four seat and early Northamerican Sabreliner

- Started by hesham

- Replies: 5

-

Armstrong Whitworth AWP.7 twin boom aircraft

- Started by hesham

- Replies: 1

-