- Joined

- 25 June 2009

- Messages

- 14,108

- Reaction score

- 4,239

Although Stanley Hiller is remembered for introducing the small practical coaxial helicopter, there was one untold American pioneer who beat him by three years, yet is all but forgotten.

Jess Dixon of Andalusia, Alabama (1886-1963), was a man continuously investigating mechanical or experimental fields, and he tinkered with almost anything mechanical. Even before receiving any formal flight training, he constructed and flew a glider of his own design that was flown successfully from Dixon airport. Tired of being tied up in traffic jams, he then devoted his efforts in 1936 to the development of a unique flying machine, a combination of automobile, helicopter, autogiro, and motorcycle. Dixon spent a lot of his spare time at the local airport with some of the early pilots and worked on gliders as well as his helicopter project. He did make a considerable contribution to the development of the machine and sought a patent on some of the apparatus that controlled the pitch of the blades. He then built a framework to hold a motor and provide a seat for the pilot.

The “Flying Ginny,” as Dixon liked to call it, was designed to allow for the transfer of engine power from the rotor blades to the wheels, which enabled its operation on surface roads. For flight and hover, it had two large lifting rotors in a single head, revolving in opposite directions, with cyclic and collective pitch control. Foot pedals actuated a hinged vane on the tail, counting on rotor downwash for yaw control. The undesignated machine could fly forward, backward or straight up, or hover in the air. It could run on road or fly across country. Although Dixon himself called it a "helicopter", it was just as much an automobile, and even required automobile license plates.

Powered by a 40 h.p. air-cooled angine, the Dixon helicopter could reach speeds to 100 m.p.h. and was supposedly test-flown in 1940-41. However, only one photograph of the type is known to exist, and although it appears that the machine is actually flying in that picture, no records have survived of the test flights. At times, Dixon would take ropes and tie the machine to the ground and the overhead blades would actually lift the machine. Initially, he had a big tail that was not enough to handle that torque, and that eventually brought about the tail fin motor.

Claims that the photo was actually retouched have since been invalidated, but in the absence of any other piece of evidence, it is hard to know whether Dixon's helicopter was as successful as he hoped. Still, the "Flying Ginny" must have been good enough since it made an impression on the Twin Coach Company of Kent, Ohio, previously known only as builders of motor buses, who hired Dixon and his machine and asked him to improve on it.

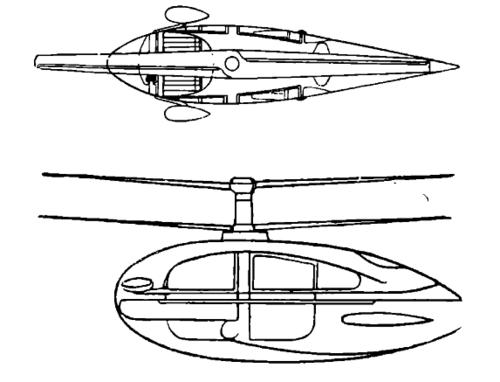

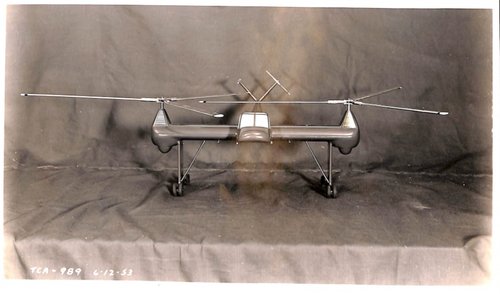

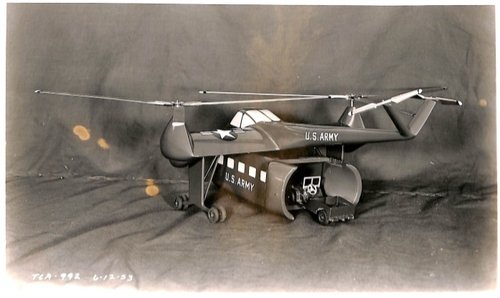

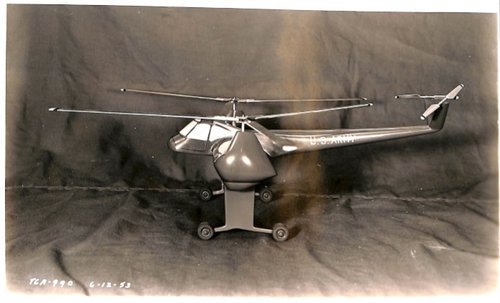

Jess Dixon moved to Ohio with his family there for about a year where he worked and continued development on the project. Like its predecessor, the new craft, designated the TCAH-1 (presumably for "Twin Coach Aircraft and Helicopters") was a superimposed coaxial twin-rotor helicopter, but it was a two-place tandem type, with one seat ahead of the engine and another behind it. It weighed 1,300 pounds and obtained its power from two 75 hp engines. Its rotors were 18 ft in diameter, and the blades of the rotors were controlled by auxiliary airfoils similar to ailerons.

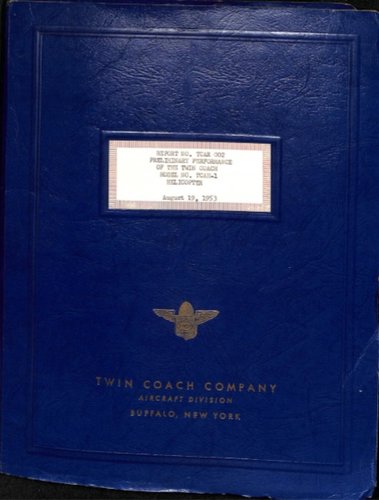

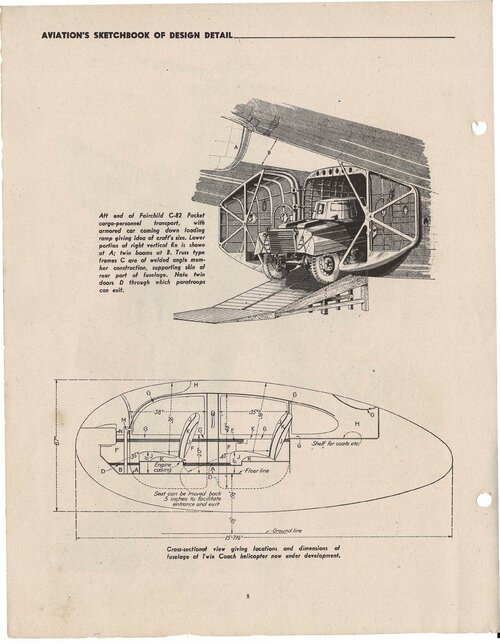

There is no evidence that the TCAH-1 ever flew, and no photos of the type are known to exist. Only a cross-sectional view, giving locations and dimensions of fuselage of the Twin Coach helicopter, was published in the February 1945 issue of Aviation (Aviation Week & Space Technology, Volume 44). However, it would appear that the Bernard Lindenbaum Vertical Flight Research Collection, located at the Wright State University, contains two reports on the type: one entitled "Model Specifications" (Report No. TCAR001, Jun 9, 1953), and the other "Preliminary Performance of the Twin Coach" (Report No. TCAR002, Aug 19, 1953), which would seem to indicate that the type was indeed test-flown.

Jess Dixon was an enthusiastic but modest rotorcraft pioneer who was fully absorbed by his copter project, yet received very little recognition for his work. It would seem that three years before Stanley Hiller, another American successfully flew a small private helicopter with coaxial rotors. For that reason alone, it's only fair that his name be added to the long list of American aviation pioneers.

Sources:

Jess Dixon of Andalusia, Alabama (1886-1963), was a man continuously investigating mechanical or experimental fields, and he tinkered with almost anything mechanical. Even before receiving any formal flight training, he constructed and flew a glider of his own design that was flown successfully from Dixon airport. Tired of being tied up in traffic jams, he then devoted his efforts in 1936 to the development of a unique flying machine, a combination of automobile, helicopter, autogiro, and motorcycle. Dixon spent a lot of his spare time at the local airport with some of the early pilots and worked on gliders as well as his helicopter project. He did make a considerable contribution to the development of the machine and sought a patent on some of the apparatus that controlled the pitch of the blades. He then built a framework to hold a motor and provide a seat for the pilot.

The “Flying Ginny,” as Dixon liked to call it, was designed to allow for the transfer of engine power from the rotor blades to the wheels, which enabled its operation on surface roads. For flight and hover, it had two large lifting rotors in a single head, revolving in opposite directions, with cyclic and collective pitch control. Foot pedals actuated a hinged vane on the tail, counting on rotor downwash for yaw control. The undesignated machine could fly forward, backward or straight up, or hover in the air. It could run on road or fly across country. Although Dixon himself called it a "helicopter", it was just as much an automobile, and even required automobile license plates.

Powered by a 40 h.p. air-cooled angine, the Dixon helicopter could reach speeds to 100 m.p.h. and was supposedly test-flown in 1940-41. However, only one photograph of the type is known to exist, and although it appears that the machine is actually flying in that picture, no records have survived of the test flights. At times, Dixon would take ropes and tie the machine to the ground and the overhead blades would actually lift the machine. Initially, he had a big tail that was not enough to handle that torque, and that eventually brought about the tail fin motor.

Claims that the photo was actually retouched have since been invalidated, but in the absence of any other piece of evidence, it is hard to know whether Dixon's helicopter was as successful as he hoped. Still, the "Flying Ginny" must have been good enough since it made an impression on the Twin Coach Company of Kent, Ohio, previously known only as builders of motor buses, who hired Dixon and his machine and asked him to improve on it.

Jess Dixon moved to Ohio with his family there for about a year where he worked and continued development on the project. Like its predecessor, the new craft, designated the TCAH-1 (presumably for "Twin Coach Aircraft and Helicopters") was a superimposed coaxial twin-rotor helicopter, but it was a two-place tandem type, with one seat ahead of the engine and another behind it. It weighed 1,300 pounds and obtained its power from two 75 hp engines. Its rotors were 18 ft in diameter, and the blades of the rotors were controlled by auxiliary airfoils similar to ailerons.

There is no evidence that the TCAH-1 ever flew, and no photos of the type are known to exist. Only a cross-sectional view, giving locations and dimensions of fuselage of the Twin Coach helicopter, was published in the February 1945 issue of Aviation (Aviation Week & Space Technology, Volume 44). However, it would appear that the Bernard Lindenbaum Vertical Flight Research Collection, located at the Wright State University, contains two reports on the type: one entitled "Model Specifications" (Report No. TCAR001, Jun 9, 1953), and the other "Preliminary Performance of the Twin Coach" (Report No. TCAR002, Aug 19, 1953), which would seem to indicate that the type was indeed test-flown.

Jess Dixon was an enthusiastic but modest rotorcraft pioneer who was fully absorbed by his copter project, yet received very little recognition for his work. It would seem that three years before Stanley Hiller, another American successfully flew a small private helicopter with coaxial rotors. For that reason alone, it's only fair that his name be added to the long list of American aviation pioneers.

Sources:

- Anything a horse can do: the story of the helicopter, Reynal & Hitchcock, 1944

- The Highway Magazine, Volumes 33 to 37, Armco Drainage & Metal Products, 1942

- Mechanix Illustrated, November 1941

- The State Library and Archives of Florida

- Aerofiles.com

- Bernard Lindenbaum Vertical Flight Research Collection (MS-364)

- Mobile Aviation, by Billy J. Singleton

- Andalusia Star News, November 19, 2008

- Andalusia Star News, January 2, 2009